By Karma T. Ngodup

Picture this: “For the estimated 3.2 billion viewers who get up early, stay up late, cheer at the television, bay at the moon, go out and beat drums in the middle of the night because somebody scored a goal halfway around the world, that’s the World Cup”. Football is truly the world’s game. It’s played in the heat of the Sahara, the jungles of the Amazon, the urban jungles of Calcutta and Los Angeles, and the manicured fields of Germany. There are some places so wild, though, that the idea of twenty-two players on a pitch seems impossible. One of those places is remote and austere Tibet, where people live at 4,500 meters altitude, on the roof of the world. Yet not only does Tibetan football have a toehold, but it also has a history.

Football made its way to Tibet as early as the early twentieth century. A photograph taken by British military officer Frederick M. Bailey—who spoke the local language and was stationed in the Chumbi Valley with Colonel Francis Younghusband as part of the 1904 British Expedition to Tibet—shows Tibetans in traditional chupa outfits, with long sleeves wrapped around their waists, posing with a football. However, it wasn’t until the establishment of the first English school in 1923 that football resurfaced in the hinterland of Tibet. Interestingly, records indicate that in 1913, four Tibetan boys traveled to London on the order of the thirteenth Dalai Lama to be educated at the Rugby School. Although they reportedly played some rugby, there is no evidence that they introduced the sport to Tibet upon their return.

The word “soccer” appeared just a year later, in 1905, in the New York Times: “It was a fad at Oxford and Cambridge to use ‘er’ at the end of many words, such as foot-er, sport-er, and as Association football, called in those days, did not take an ‘er’ easily, it was, and is, sometimes spoken of as Soccer.” Today, the game is known by many names: football for some, Fussball or futbol for others. Whatever we may call it, it is the ball that bears the brunt of the kick. The word spo lo (ball) is not new in the Tibetan vocabulary. Surprisingly, the modern game of polo is said to have originated in Tibet in the 7th century, with the word deriving from the Tibetan word pulu, meaning ball. However, for the sake of clarity and to reach out to the wider world, where the game is commonly known as football, it is referred to as such by most of the Tibetan community in the Diaspora.

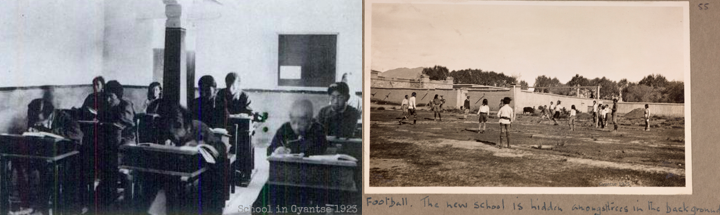

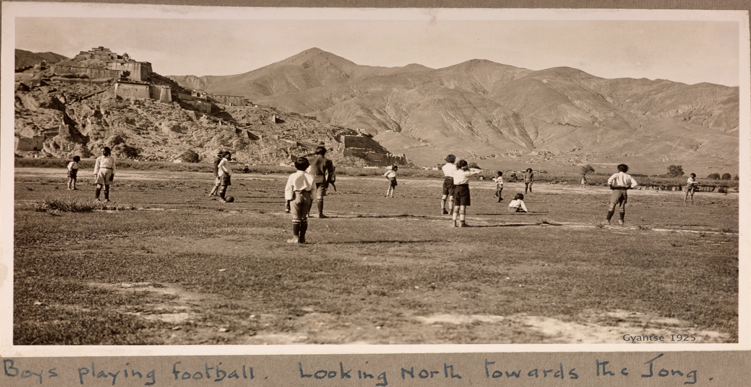

Football began in Tibet in earnest with the English School in Gyantse in 1923, when Frank Ludlow (an Englishman), became the headmaster of the school. As Ludlow chronicles in his diary:

By the end of November, 30 boys had arrived, aged 8 to 18. Some of them were charming kiddies, well-bred and well clothed. Others were not so prepossessing and evidently came of more plebeian stock. I got the boys to seat themselves at my rather primitive benches and had one or two cut down to suit their size. Everybody was so solemn whilst this was being done, and the boys looked so glum, that I fished out a couple of footballs and told all except 2 or 3 to go out and play in the compound. This worked wonders, and five minutes later when I went out I found them running all over the place, laughing and chattering in the very best of spirits…

Ludlow had been a member of his college football team at Cambridge. Ludlow’s enthusiasm for football even reached the ears of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, who asked about the result of a match between the school and an army team (the school lost 2-1), and then “enquired if it was true that I was very fond of ‘kicking the ball with my head!”

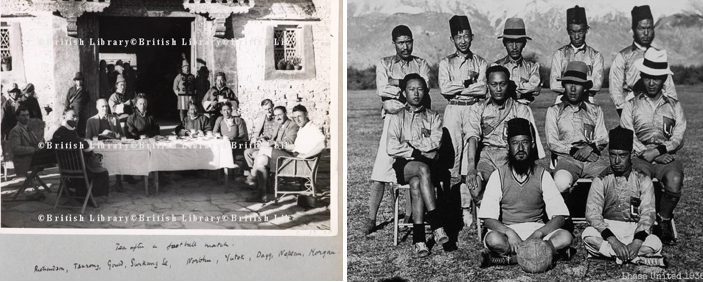

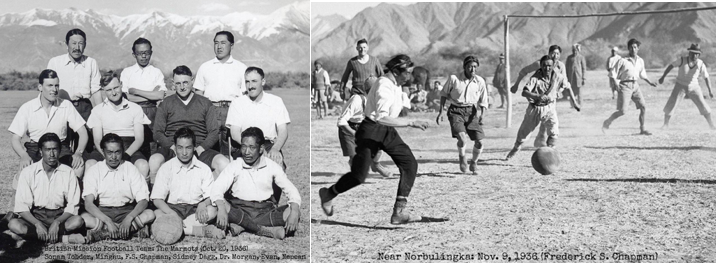

That the game of football persisted through the 1930s can be seen in British officer Frederick Spencer Chapman’s description of a match against Lhasa United in October 1936:

Today we were challenged to a game of “Football” by Lhasa United, a team consist of Nepali soldier, a Chinese tailor, three bearded Ladakis, a Sikkimese clerk of Pangda-Tsang, and five Tibetan officials including Yutok, Surkhang-Se, Taring, (other two maybe Ragashar and Shelling). They turned out in garish Harlequin-coloured silk shirts with L.U. sewn on to the pockets. After a good, clean, hard game the Mission Marmots (as we call ourselves) won by scoring the only goal of the day. Playing at 11,800 feet is not as much of an ordeal as one would imagine, and we appeared to be no more breathless than our opponents.

Today we were challenged to a game of “Football” by Lhasa United, a team consist of Nepali soldier, a Chinese tailor, three bearded Ladakis, a Sikkimese clerk of Pangda-Tsang, and five Tibetan officials including Yutok, Surkhang-Se, Taring, (other two maybe Ragashar and Shelling). They turned out in garish Harlequin-coloured silk shirts with L.U. sewn on to the pockets. After a good, clean, hard game the Mission Marmots (as we call ourselves) won by scoring the only goal of the day. Playing at 11,800 feet is not as much of an ordeal as one would imagine, and we appeared to be no more breathless than our opponents.

Football continued in Tibet with teams such as Lhasa United, Mission Marmot, and Drapchi until 1944, when the sport was abruptly banned. A hailstorm during a game was interpreted as a bad omen, leading the monastic establishment to persuade the regent to issue a decree that declared kicking a football “as bad as kicking the head of Buddha.” Such an act was not unprecedented: even in Britain, where football is now a major sport, King Edward II issued a proclamation in 1314 banning football due to “great noise in the city caused by hustling over large balls from which many evils may arise which God forbid.” Centuries later, Shakespeare used the term “football” disapprovingly in King Lear, writing, “Nor tripped neither, you base football player.”

By the end of the Second World War, football was on the verge of a significant rise in Tibet. Popular clubs such as Lhasa, Potala, Drapchi, and the Bodyguard Regiment football teams emerged. There were as many as fourteen squads, although a formal Tibetan League had not yet been established. Today, some of the former team members live to old age, watching every football game that comes their way. Last year, I encountered an old man waiting for a ride to GCM in Dharamsala, only to discover he was Tashi Tsering, a former Drapchi player. Then there’s our TCV Gyen Thupten la, who still cherishes his memories by attending GCM events as a guest.

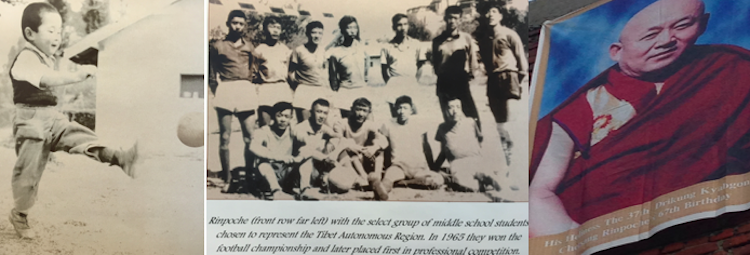

Following the Tibetan National Uprising on March 10, 1959, football survived amidst the waves of modernization, as Drigung Chetsang Rinpoche discusses in his biography. Rinpoche himself was known for his remarkable football skills, often referred to as having “a golden foot.” From childhood onwards, Rinpoche has harbored a great passion for football. What more nostalgic gift could there be to celebrate his birthday than a football tournament? Every year, like clockwork, young boys in Dekyiling hang their football cleats on their shoulders and eagerly await the call to the pitch. Not far from there, one of the most prominent football clubs in exile, based in Clementown, organizes a memorial tournament for Paltrul Rinpoche.

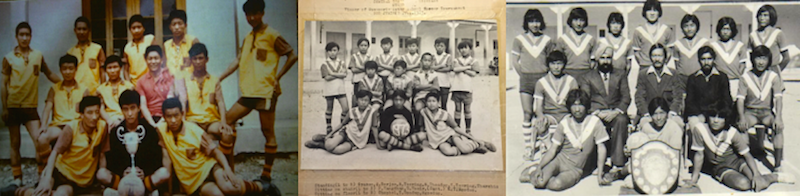

First, let me take you back to 1960, when the first Tibetan school was opened in Mussoorie, India. Football quickly became the favorite pastime of the exiled students. Many of these students had left Tibet with little more than the clothes on their backs, and they were reduced to playing barefoot with balls fashioned from rags and socks. Time on the pitch allowed them to forget, at least temporarily, their arduous journeys and tragic histories. Their devotion to the game was so strong that, in 1968, they won the interschool championship among some of the best international and private schools in India..

Here it may suffice to describe how inspiring this triumph was for a young football player like myself; the story propelled my teammates and me toward victory in our first sub-junior football cup. Stories of that team are ever-present in my old school, where photographs of the team still hang in the corridors. One can imagine similar stories and photos in many other schools of the time.

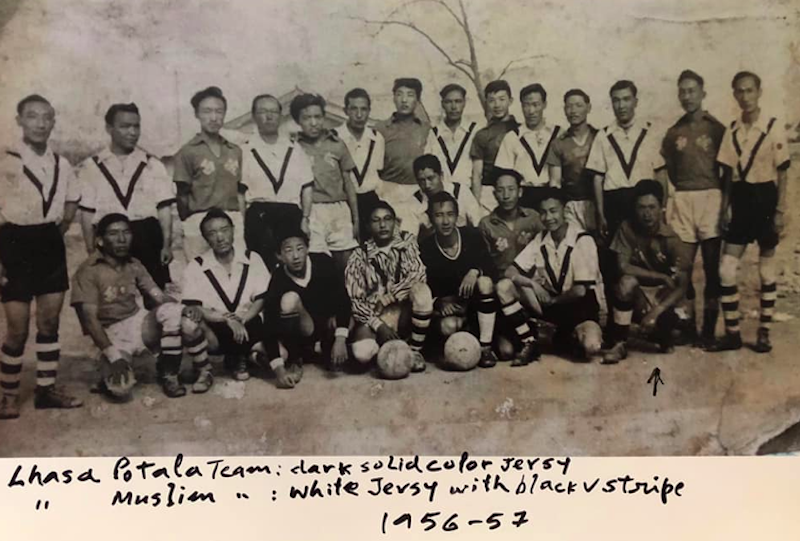

Some time ago, Mrs. Khando Chatsotsang shared a historic photo that intrigued me for three reasons. First, there were no known photos of football in Tibet during the period of 1956-57. Second, the photo addresses my long-standing curiosity about why our school football uniform resembles that of one of the world’s top clubs, Manchester United. Lastly, the photo is personally nostalgic, as I remember seeing the passionate footballer Kungo Rabten Chazotsang always playing on the left flank for the staff team, inspiring us early in our lives. However, we were unaware of this part of the history.

Possibly the most notable part of the photo was the uniforms the players wore. Uniforms are about more than aesthetics. I was told that the solid color of the Tibetan jersey (Lhasa Potala team) was maroon, probably symbolizing allegiance to the faith. The jersey of the Muslim team, on the other hand, was white with a single V stripe running from the shoulder to the middle of the chest. This was very interesting, as it may provide answers about some of the photos of our early school teams. Although Tibet has never been a market for Manchester textiles, there is a kind of Manchester in the uniform.

Back in 1973, when we won the first interschool football championship in Mussoorie, we were wearing white striped shirts with laces. This school uniform was the only one that lasted for decades to come. This photo likely shows that these school football jerseys with a V-stripe running across the chest were not arbitrary but rather an idea that originated long ago in Tibet. Notably, the similarity extends to the socks and even the laces on the jerseys. The V-stripe jersey, also known as a chevron due to its “V” pattern, was first worn by Manchester United in their inaugural winning match against Bristol in 1909.

During this period, two prominent Tibetan football clubs emerged in Nepal: Potala and Norbulingka Football Clubs. Both clubs became elite participants in Tibetan football tournaments held in Mussoorie and Dharamsala, reflecting the strong passion for football within the Tibetan community.

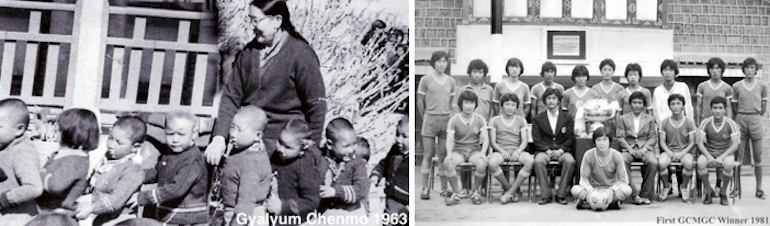

So when the great mother of H.H. the Dalai Lama passed away in 1981, Tibetans in Dharamsala inaugurated the Gyalyum Chenmo Memorial Gold Cup (GCMGC) Football Tournament in her memory, with an iconic trophy made from gold and silver and studded with semi-precious stones. The Tibetan people wanted to express their love and respect for the Great Mother and to remember her kindness, and there was no better way than through the game so many Tibetans love so passionately. The first GCMGC tournament took place at the Tibetan Children’s Village grounds in October of 1981. The first cup was designed at the Tibetan Handicraft Center (Tengshel) near Lower TCV, with stones from the private office of H.H. the Dalai Lama.

Tibetan football continued to thrive locally in the decades to come, but a major leap forward was made in 1998. That year, in response to an invitation from the Italian rock music group Dinamorock, a Tibetan national team was formed to compete in Bologna, Italy, the next year, an effort in which Kasur Jetsun Pema played an instrumental role. This was a turning point for Tibetan football, as so many talented players had nurtured quiet dreams of playing for a Tibetan National Team. Around this same time, the Danish trekker Michael Nybrant conceived of a Tibetan National Team tour, and went on to play a pivotal role in arranging the national team’s successful and historic series of matches in Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland, in 2001.

Prior to the European tour, the squad had an audience with H.H. the Dalai Lama in which he expressed curiosity as to whether the national teams of India, Nepal, and Bhutan had similar opportunities to play abroad. At the time, I immediately felt his signature style of spontaneity, reminding our players of how fortunate they were to travel to and play in countries where football is not merely a game, but a way of life.

With those visits to Europe, the doors to the football world finally opened for Tibet. Shortly after, the Tibetan National Team toured France in 2003 and even made contact with representatives from FIFA. This encounter ultimately led to FIFA awarding Tibet its first-ever FIFA ranking (175), which lasted only two days in 2004 before being removed due to numerous complaints from China’s sports authority. FIFA later stated in a letter that the decision was based on Tibet “not fulfilling the requirement” to be a member. However, this international recognition led to further positive developments in 2006 during the World Cup. Barred from qualifying for the FIFA World Cup by China’s refusal to allow Tibet to field its own squad, the Tibetan National Team traveled to Germany to participate in the parallel international competition known as the FIFI Wild Cup. This event, administered by the Federation of International Football Independents (FIFI), featured teams from nations not yet recognized by FIFA as well as FIFA member teams from the Asian Football Confederation. In 2008, the national team toured Europe again, playing eight international matches.

As the years have passed, a new generation of young Tibetan girls has emerged in the sport. These young women play with the same intensity as the men, participating in numerous matches and even successfully hosting a CONIFA Women’s Cup in India. The Tibetan Women’s team has made several trips abroad, with the next one scheduled for June, where they will compete in the CONIFA Women’s World Cup in Norway. The recent Women’s World Cup has already inspired a generation of young girls to aspire to become the next Bonmati, Alex Morgan, or Sam Kerr. The day will undoubtedly come when Tibetan women achieve their own successes in competitive football.

That inspiration can be drawn from such events that will fuel a future football boom in the Tibetan diaspora can be seen in this wonderful photograph of young fan captured during a GCMGC at Dharamsala. Probably, these fans explain best the young monk Ogyen’s obsession with football in movie “The Cup” as one review states thus: “beneath his maroon monastic robes, sports a tank top on which he has emblazoned the name and number of Ronaldo, the Brazilian star.

Besides the GCM, Tibetan football is gaining traction within the community through several high-profile tournaments such as the South Cup in India, the Euro Cup in Belgium, and the Dalai Lama Cup in New York. With ample opportunities evident, young enthusiasts should view football not just as a pastime robtse, but as a potential livelihood that has created employment opportunities across the Western world.

One of the prominent platforms aiding this growth is CONIFA (the Confederation of Independent Football Associations), which supports all football associations outside FIFA. This organization aims to prepare its affiliated members for international competitions by arranging administrative structures and matches to meet the FIFA admission requirements where possible. The CONIFA platform is what we need for Tibet as a nation to represent in international competitions, providing Tibetan players with unique experiences that can help them find opportunities in European football.

GCM India is happening right now at the Tibetan Settlement of Hunsur Rabgyaling with games getting into quarter finals. This time the challenge seems to be caused due to rain where the pitch becomes slick and muddy, making ball control and footing more difficult.

The sound of the rain, combined with the cheers and shouts, creates a distinctive auditory backdrop. Yet, the players endured, ensuring the tournament would successfully conclude on time. The Tibetan Youth Soccer Tournament is set to debut with regional tournaments in Utah, the West Coast, Chicago Midwest, Toronto, and New York. The aim is to select a team to represent Tibet Boys at the Dallas International Youth Soccer Tournament in April 2025..

The Tibetan Youth Soccer Tournament is set to debut with regional tournaments in Utah, the West Coast, Chicago Midwest, Toronto, and New York. The aim is to select a team to represent Tibet Boys at the Dallas International Youth Soccer Tournament in April 2025..

The best is certainly yet to come. The GCMGC North America is returning to Toronto after eight years in 2024. We are getting closer to seeing Tibetan players tapped for Major League Soccer (MLS) in North America, or even the British Premier League or Bundesliga. The day will come when we will witness our own Messi, Mbappe, or Mitoma. Let’s dream and hope that one day, when half the world rises early and beats the drums of victory across the globe, it will be in celebration of a Tibetan goal.

But we are not done yet. Recently, another unique initiative emerged from a significant section of the Tibetan diaspora, as identified in our demographic survey. Individuals aed over 40, who play crucial civic and entrepreneurial roles in our community, have taken a remarkable step. Earlier this year, they established the ALL Pala Football Association to relive and celebrate the glory of their youth. They are organizing the APFA Gold Cup on Father’s Day this year—the first of its kind—promoting health and happiness within the Tibetan community through the beautiful game of football.

Note: The Article is revisited with new information and images from the British library

(Views expressed are his own)

The author is a coordinator of Tibetan National Sports Association in North America.

Notes:

- Arthur Hopkinson’s diary (British Trade agent in Gyantse 1927-28):

Sat. April 9, 1927: Played football and tennis [A. J. Hopkinson Archive, OIOC British Library, Mss Eur D998/54, Journal Letters from Gyantse and Various Camps, 1927-28, commencing April 7th 1927, Yatung, page 3]

- Thursday, April 14, 1927:Played football in early morning. Had lunch with Depon, accompanied by Vance [A. J. Hopkinson Archive, OIOC British Library, Mss Eur D998/54, Journal Letters from Gyantse and Various Camps, 1927-28, commencing April 14th 1927, Yatung, page 1].

References:

- British Library Collections: Bailey, Frederick Marshman. Tibetan football team, Chumbi., Photo 1083/17(206) 27 Jan 1907

- British Library Collections: Frank Ludlow’s Album Photo 743/4(20), (54), (55) Football at Gyantse, 1924

- Vecsey, George. “Sports of The Times; Six Months to Obsess About World Cup Schedule.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 06 Dec. 1997.

- “Tibetan National Sports Association.” Tibetan National Sports Association. Tibetan Children’s Village, 10 Mar. 2003. Web. 28 Apr. 2016.

- Frank Kingdon-Ward by Charles Lyte (London, 1989), p. 70, Lord Cawdor’s diary quotes “I played for the Tibetan team.”

- “King Arthur Comes To Tibet: Frank Ludlow and the English School in Gyantse, 1923-26.” Academia.edu.

- Ludlow diary (1923-1946) British Library, Oriental and India Office Collection (OIOC), Mss 979

- Freeman, C. (2006) The Tibetan Album: British Photography in Central Tibet 1920–1950.

- Modern polo is derived from the Tibetan game. rta pu lu (horse ball) played in Tibet as early as in the 7th century.

- “Tibetan Pulu”, originally appearing in Volume V22, Page 12 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.

- From the Heart of Tibet: The Biography of Drikung Chetsang Rinpoche, the Holder of the Drikung Kagyu Lineage, August 10, 2010

- Pitt Rivers Museum, Harris, C., Tsering Shakya,. Seeing Lhasa: British Depictions of the Tibetan Capital, 1936-1947. Chicago: Serindia, 2003. Print.

- Shakespeare, William, and Horace Howard Furness. King Lear. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1880.

- Cashmore, Ernest Ellis. Making Sense of Sports. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2010. Print.

- McKay, A. “‘Kicking the Buddha’s Head’: India, Tibet and footballing colonialism.” Football and Society 2, no. 2 (2001): 89-104.

3 Responses

Reting Rinpoche knew that British people were there to deceive us by using football as a weapon to softten our hearts, and establish camadarity. So he righly cancelled football from Tibet to prevent british inteference in the internal matter of tibet. There were two sections in Tibet government at that time – an anglophile group and a sinophile group. but both groups deep down trusted neither the British nor the Chinese government, as both were considered deceivers, and want to eat and steal. Tibet did not want any interactions with anyone else fromt he wr invasion. Tibet never welcome any form of intervention by third parties in the world, for we tibetans are and were best in the world. we know all the rest of the world are liars, and evil. No foreigners are trusted in Tibet, all are liars in our eyes. We Tibetans pity foreigners for how little they know about science of the mind, and how shalllow western psychology originated from Sigmund Frued and Carl Jung are, if pitted against big books like Tibetan book of the Dead etc. western capitalist civilization is barbarians compared to tibetan civilization.

Don’t trust white people. They have lied and colonized poor african black people and indians etc in the last few hundred years, and emasculated these poor helpless coloured humans. We Tibetans support all human beings irrespective of colour, we tibetans are kind and big-hearted, we are not like white colonizers. we are above these people. we follow hh dalai lama, and we believe in kindness, compassion, empathy, and saving other people, not killing them. We Tibetans are not killers, we don’t kill. human planet earth is going mad, only we Tibetans can stop these mad, delusional, sadistic, violent people from wars and killing one another. we are their daddy, those delusional people know don’t know about teachings of Sithartha Gauman Buddha from India 2,500 years ago about compassion.

An excellent chronicle of the history of Tibetan soccer! I especially enjoyed the supporting photographs, as I imagine most Tibetans like myself have never seen these photos before. This research is great and I am very excited for the future of soccer for Tibetan men and women after reading this.