By Tsunma Rangrig Dolma, a Tibetan Buddhist nun

A critique of Sonia’s Feleiro’s “The dangerous rise of Buddhist extremism: ‘Attaining nirvana can wait,’” published by the Guardian on November 26th, 2025 and why it misses the mark.

There is an exhausting genre in modern journalism: the “Buddhism isn’t what you thought” long read. It arrives with moral seriousness, a scenic travelogue and crucially, a rush to flatten 2,500 years of religious history and diversity into one tidy problem. Sonia Faleiro’s article in the Guardian “The dangerous rise of Buddhist extremism: ‘Attaining nirvana can wait” does this with exceptional bravour, folding Theravadan Politics in Myanmar and Sri Lanka, Tibetan exile and tragedy and Silicon Valley woke meditation culture into a single, neat narrative, that explains little but distorts a lot.

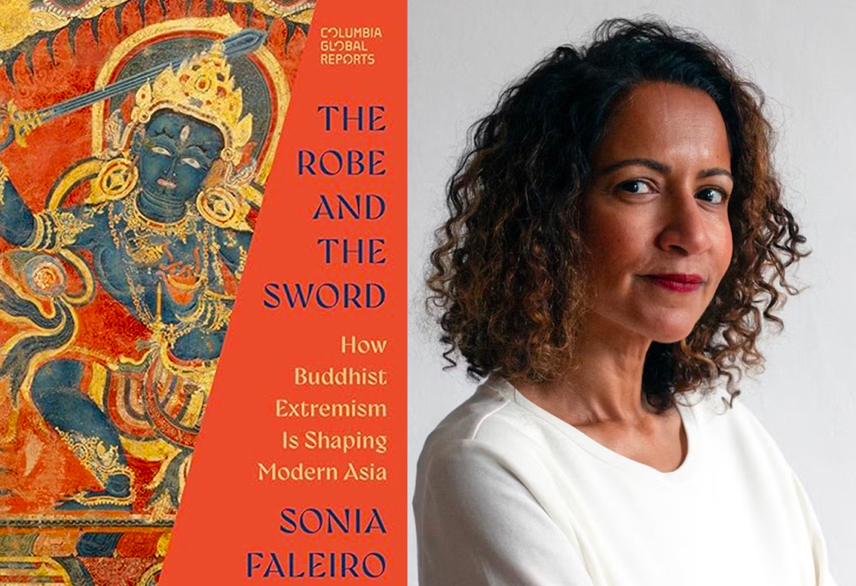

The timing is no mystery. The article functions conveniently as a promotional runway for Faleiro’s new book, The Robe and the Sword: How Buddhist Extremism Is Shaping Modern Asia (published November 11th 2025, Columbia Global Reports), which investigates the role of Buddhism in extremist movements in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand. Fair enough; authors need publicity. But in the process, Faleiro drags Tibetan Buddhism into the frame as if it were part of the same phenomenon, while in reality, this is not the case.

This is not to dismiss the very real problem of faith being co-opted for violence or the existence of patriarchal patterns within some Buddhist communities. It is to insist that the problem be treated with the precision it deserves: separate the Dharma from opportunistic politics, stop using Tibetan suffering as rhetorical seasoning and acknowledge the real progress, particularly by women, happening inside Tibetan Buddhist communities and institutions.

What follows is an attempt to untangle this confusion: to examine how Faleiro misappropriates Tibetan Buddhism for rhetorical effect and why her observations about Tibetan Buddhist culture and practice are not just misinformed but often dramatically miss the mark.

Mixing Traditions and Missing the Irony

A central problem with the article is that it treats Buddhism as if it were a stable political identity, rather than a spiritual path grounded in the Dharma. It mixes the actions of militant monks in Sri Lanka or Myanmar, tragic self-immolations in Tibet, Himalayan monastic history and Google mindfulness culture into a single narrative of “Buddhist extremism.”

But the truth is: while there is one Buddhism and one Dharma, how human beings interpret, practice and politicise it can vary enormously. The misuse of the Dharma for political gain, ethnic majoritarianism, or communal violence does not reflect the Dharma itself. It reflects human weakness, fear, greed and ignorance.

What’s especially ironic is that the author repeatedly criticises Western commentators for “throwing everything into one pot,” yet she herself performs exactly that same sleight of hand. By blending centuries of distinct lineages, practices and cultural contexts into a single story, the piece ends up doing precisely what it claims to critique – oversimplifying a vast, complex and inherently diverse religious tradition.

What we need instead is clarity about which tradition we are discussing, not a catch-all “Buddhism did this” headline.

Tibet as Exotic Decoration – Again

The article often invokes scenic and mystical stories of Tibet – a 1913 Tibetan army, the Dalai Lama’s flight from Tibet on horseback, the quiet and serene atmosphere of McLeod Ganj, contrasted with monks setting themselves on fire and mythical bodhisattva legends – and uses them as evidence for a Buddhist violent history when talking about Sinhala-Buddhist riots or Buddhist mobs in Myanmar. These Tibetan references appear less as serious historical context and more as dramatic seasoning: exotic, tragic and most importantly, emotionally potent.

But while Tibetan history and political suffering are real, they do not belong as supporting evidence for something happening in a context as different as Sinhala-majority Sri Lanka or Buddhist-majority Myanmar. Using Tibetan tragedy as collateral for a broad claim about Buddhist “militancy” in other traditions is not only inaccurate. It is disrespectful to the people whose histories are being used for dramatic effect to sell a book.

Self-Immolation: Tragedy, Not Doctrine

In particular, the article’s treatment of Tibetan self-immolation is deeply disturbing and misleading. It quotes a self-immolator, a former monk, who parallels his protest of setting himself on fire to the actions of the Bodhisattva in the Jākata Tales. In this story, the bodhisattva offers his own body to save the starving cubs of a tigress. The former monk suggests this to be some kind of doctrinal instruction. However, this interpretation, which Feleiro accepts without doing her own due diligence, misses three critical points:

The Jātaka tales (including the tigress story) are symbolic moral stories, not prescriptive manuals. Their purpose has always been to illustrate extreme compassion and the bodhisattva ideal, not to instruct ordinary beings under duress to self-immolate.

The core Buddhist precepts, starting with Pāṇātipātā veramaṇī sikkhāpadaṃ samādiyāmi (“I undertake the precept to abstain from killing living beings”), cover all intentional taking of life. That includes one’s own. Suicide and self-harm fundamentally lie outside the ethical path the Buddha laid down.

Within Tibetan exile and monastic communities, self-immolations are almost universally met not with praise or divine interpretation, but with grief and seen as tragedies, reminders of oppression and despair, not heroic theology.

Framing self-immolation as spiritual martyrdom or doctrinal authenticity is not compassion; it is spectacle. Buddhist teaching has always valued preserving life and showing compassion to all beings. To treat these tragic acts as theological statements is to distort the Dharma for rhetorical ends.

While we have established that self-immolition has no tangible foundation in the Buddha’s teachings, there is one overlooked fact that deserves sober acknowledgment. In the long and grim history of political violence, acts of protest often involve harming others. From suicide bombings to the orchestrated horror of attacks like 9/11, individuals have used their own deaths as weapons against others. Tibetan self-immolators, by contrast, directed their self-destruction only toward themselves.

This does not make the act noble, correct, or sanctioned. It simply underscores a distinction Faleiro’s article fails to recognise: Tibetan self-immolation is political, yet nonetheless a cry born of despair. It is not a campaign of violence and to conflate it with religious doctrine is not analysis, but a categorical error.

Gender and Ordination: The Overdue Progress That the Article Missed

Faleiro also presents sexism as if it were frozen in amber, an ancestral wound that everyone in Tibetan Buddhism still bleeds from. However, the reality is much more dynamic.

In fact, the last 15 years have seen historic breakthroughs for women’s education and ordination:

Geshema degree: Since 2012, Tibetan Buddhist nuns have been earning the Geshema title — the highest scholastic degree in monastic philosophy in the Gelug School, equivalent to the Geshe (male) degree. Dozens have completed the rigorous curriculum and examinations.

Khenmo degree: In the Kagyu, Nyingma and Sakya traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, women have begun receiving khenmo degrees — the equivalent of the male khenpo — recognising their scholarly authority, teaching capacity and monastic leadership.

Full ordination (Gelongma/ Bhikshuni revival): In places where full female ordination had disappeared, the Tibetan tradition is now restoring it with remarkable momentum. Under the guidance of senior lineage holders, full Gelongma ordination has been formally re-established. In a historic milestone, the second cohort of fully ordained Gelongmas received ordination in Bhutan on November 19th, marking a decisive step toward full equality for Tibetan Buddhist nuns.

Women leading real institutions: Nuns run nunneries, teach philosophy, translate scripture, engage in community outreach and participate fully in monastic life. Female leadership is growing, not symbolic.

Contrary to the article’s implication of stagnation, women are now founding nunneries, teaching philosophy, leading communities and participating in the fourfold sangha — a reality that deserves recognition, not erasure.

Bell hooks wants her context back!

One of the more ironic passages in the article quotes bell hooks as if she were condemning Asian Buddhism generally. But in truth, bell hooks was describing her personal experiences in some American Buddhist communities, critiquing racial dynamics, the commodification of spirituality and the ways Buddhism in the West can be shaped by systemic whiteness and privilege.

To reuse her critique to indict Theravada monks in Sri Lanka or nuns in Tibet is to take her voice out of context entirely. It’s like quoting Malala Yousafzai’s advocacy for girls’ education in Pakistan to argue that all education systems worldwide are inherently oppressive. The author of the article is therefore using a powerful voice for a purpose the speaker never intended.

In summary, quoting bell hooks about Western sangha problems to prove that Asian Buddhist traditions are inherently flawed is rhetorical deception. This noticeably undermines both Faleiro’s insight and credibility, as well as the diversity of Buddhist communities globally.

The Dharma Isn’t the Problem – People Are

At heart, Buddhist teachings of the Dharma are not political packaging. Its foundation rests on the precepts, on the cultivation of compassion (mettā), on understanding interconnectedness (pratītyasamutpāda) and on non-harming.

When monks or nuns misuse identity, robes or religious authority to commit violence, hatred, oppression or even misconduct, the culprit is not the Dharma. It is human greed, fear, power-hunger and social conditioning.

As ancient teachings and modern ordination reforms show, the possibility for genuine spiritual life in Buddhism remains robust, pure and alive. That even when human beings occasionally turn it into something ugly.

Conclusion: Complexity, Not Simplification

Yes, some Buddhist-majority countries have seen violence, nationalistic appropriation and gender injustice. These things deserve thoughtful critique. But in trying to expose those dangers, Faleiro’s article ends up repeating the very errors it claims to confront: sweeping generalisation, misappropriation of suffering, flattening of difference and refusal to see the many Buddhist traditions that exist.

If we care about justice and truth, we owe it to Buddhism and to ourselves, to treat its teachings and communities with nuance, respect and humility.

Because the Dharma is not broken.

Some of us are.

But with care, study and compassion, that can change.

(Views expressed are her own)

The author is Tibetan Buddhist nun from Germany, ordained in the Karma Kagyu lineage. She is currently studying Tibetan language at Sarah College in Dharamshala while living in the Tibetan and Sangha community. Her main interests are meditation, applied Buddhist practice and monastic study. Before ordaining, she worked in finance and management and holds a bachelor’s degree in Liberal Arts and a master’s degree in Management from the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom.

8 Responses

I think this review misses the mark, arguing against strawmen and imagined slights not the actual contents of the book.

The books author quotes a Tibetan self immolation survivor and you fault the author for what she quoted because you disagree with the self immolators take on a Buddhist tale. Surely he has the right to his view point and to speak without you telling us that he has misunderstood a fable and that in fact your interpretation is the correct one? And even if he somehow is “wrong” should the author have changed the quote to appease your feelings? He said it and she quotes him, why are you trying to drown out the voice of such a brave man?

Perhaps revisiting the book with more patience would be helpful.

Here is a more insightful review, which coincidentally contradicts many of your points.

https://tsamtruk.com/2025/12/05/book-review-the-robe-and-the-sword-how-buddhist-extremism-is-shaping-modern-asia-by-sonia-faleiro/

Whoever wrote the anon review for GATPM but more seriously, whoever published it at the latter, should revisit the book and read it against this anon review. This revisionist anon review account of what the author means is really not what is in the book? GATPM needs to up its own editorial standards of publication, especially where Tibetan affairs are concerned…

For starters, if I were reviewing this book myself for the India / Tibet bits – and I am not – how can a book on ‘Buddhist Extremism in Modern Asia’ not include a single word about China (or indeed, Tibet’s struggle against China, except what was published by The Guardian – there is nothing of their great non-violent resistance and comparison with extremist Buddhist majority countries in the book, contrary to what this anon review says and cites?)

Also,

https://www.phayul.com/2025/12/04/53394/

The deafening silence of the author in her book and the “deafening silence of the majority” on the above kinds of everyday atrocities against monastics shaping the whole of modern Asia need to be raised by GATPM, I should think, rather than the poor editorial decision to publish this anon review for whatever reasons best known to them. ?

Tibetan self-immolators never intended to hurt others, including their tormentors; they were willing to sacrifice their lives to demonstrate Chinese communist party’s inhumane treatment and oppression against Tibetans and other minorities. It is very sad that more than 100 Tibetans lost their lives; in particular, most of them were very young. Now CCP must give real freedom to Tibetans and other minorities; let freedom ring in Tibet, Inner Mongolia, East Turkistan and Hong Kong!

Ann sun suki from burma is a pretender, is not at tibetan level, has abused people and is evil and her Nobel prize must be taken back. She thought she can fool everyone and she is wrong. Gender doesn’t matter, there’s a deceitful human being.

Extremely good explanation by Hardcore Nationalist!! This is my understanding of Mahayana Buddhism and the Dharma, having lived in India 18 years.

why tibetan female children are not joining nunnery as nuns these days, despite opportunity to become Geshe-ma or female Geshe? Most of them are becoming nurses in america or europe instead of nuns in india or nepal or tibet.

Whoever is Sonia Faleiro, she obviously has an axe to grind against Buddhism! She is either a proxy of anti-Buddhist communist China, an evangelical Christian or an attention seeker to grab the headlines with cheap pot shots against Buddhism. Buddhism has been here on earth longer than any other religion. It spread all across the Asian continent including Tibet, Mongolia, Japan, Korea and China. It is a very diverse philosophy of life rather a religion. Fundamentally, it has two main schools of Mahayana School and Theravada School. The Mahayana spread to Tibet and Mongolia while the Theravada spread into South Asia region. Japan and China have their own traditions which are a mix of their own indigenous beliefs co-existing with Buddhism. The difference between Mahayana Buddhism and Theravada is: the former adherents seek to achieve liberation for all beings while the later adherents seek individual liberation. However, there is no contradiction between the two. In order to seek liberation of all sentient beings, one must first go through the practise of the tenet of the individual liberation seeker such the practice of Four Noble Truth. THE FOUNDATION OF BUDDHIST PRACTISE IS NON-VIOLENCE! This is the bedrock of Dharma practice. Both the Theravada practitioner and Mahayana practitioner are wedded to the practise of Ahimsa! AS IT WERE BUDDHISM IS THE MOST PEACEFUL RELIGION IN THE WORLD! It has no history of violence such as inquisition, stoning women to death for adultery or honour killings. It accepts all people from all walks of life to their temples, shrines or monasteries without discrimination on the basis of their caste! IT EMBRACES NOT ONLY ALL HUMANITY BUT EVEN THE LESSER BEINGS LIKE ANIMALS AS WORTHY OF RESPECT AND COMPASSION. In fact special emphasis is laid to demonstrate more care and compassion to those who are destitute, down-trodden and trampled upon by others. As a result of such warmth and kindness, it has attracted millions of people in the Asian continent but it spread to the west and beyond. The British poet Sir Edwin Arnold proclaimed the Buddha as the “LIGHT OF ASIA”. Since the brutal and illegal occupation of Tibet by communist China, The Dalai Lama has been instrumental in bringing Buddhism to the entire west including the African continent. Hundreds of European young men and women have joined Buddhist monasteries in India which have been re-established in exile. Today, there are hundreds of Tibetan Buddhist centres across the world. There are even more Sri Lankan, Thai and Burmese Buddhist centres around the world. Both male and female devotees can get ordained. Sonia Falerio’s article cherry picked some of the events in Burma during the Rohingya crises spearheaded by the Burmese junta. One Burmese monk who was in the forefront of the violence against Rohingya was portrayed by the western media as “Buddhist Hitler”. Angsang Sukyi had to go to the International criminal court to explain the cause of the violence against the Rohingya community. The western leaders talked about stripping Angsang Sukyi of her noble peace prize accolade! They claimed it was genocide! However, when Netanyahu has killed more than 64,000 Palestinians mostly children and the ICC indicted Netanyahu of crimes against humanity, he is still enjoying immunity from those who are the self-declared defenders of human rights! The Burmese monks did not kill Rohingyas! The death of Rohingyas who were killed were no where near the astounding number of Palestinian death at the hands of Netanyahu and his Israeli IDF. The lady in question has the same level of hypocrisy when it comes to the so called “Buddhist extremism” that she attempted to peddle to disparage Buddhism. She purposely dragged Tibetan Buddhism when Tibetans have done nothing to hurt others except to kill oneself to highlight the unimaginable oppression perpetrated by the Chinese communist regime in occupied Tibet. Those 160 Tibetans who have self-immolated did not commit violence against the Chinese occupiers of our country. Since, protests of any kind are banned in occupied Tibet and even if one did protest, the protester will be killed anyway through torture and incarceration which leads to custodial death. Owing to this reason, there is no other way to highlight the dire situation in occupied Tibet by than a quick death by burning oneself. What is important to note here is this. Whether, the act can be construed as violence or not depends on the motivation according Buddhist canonical doctrine. Tibetan self-immolator’s motivation is not driven by hatred against the Chinese enemy but it is in the spirit of saving the Holy Dharma and the Tibetan people from oppression. Dharma had played a pivotal role in their personal life which is being erased and destroyed by the Chinese communists. In order to highlight this grim tragedy, they burned themselves! Instead of understanding this phenomena, the lady sees it as violence. This is another western hypocrisy whereby when it suits their agenda, they will have a different interpretation. Remember, how the west hailed the self-immolation of the Vietnamese monk Thich Quang during the thick of the American anti-communist war in Vietnam. He was hailed as a hero that changed the course of the war! However, when Tibetans are doing the same to highlight the oppression by communist China, instead of showing solidarity and sympathy for the victims and Tibetans, she interprets it as Buddhist “extremism”!!! It is much easier to kill others than oneself. We see how so many radical Islamists drap themselves with suicide vests and detonate them in public places to cause maximum casualties. Tibetans believe in ahimsa and are against killing others, that’s why they only kill themselves for the good of their people and to save the holy Dharma from being destroyed by foreign occupier, anti-Buddhist and anti-religious communist totalitarian regime of China!

Wonderful analysis of the faults in the original article.