By Mayank Chhaya

Four and a half decades after he was forced to flee his homeland in the face of annexation by China, the Dalai Lama is as distant now from an independent Tibet as he was then.

Now 68, the spiritual and political leader has spent the past 15 years touring the Western world to campaign for Tibet’s independence through peaceful means. He has been courted by powerful world leaders and feted by Hollywood celebrities. He has drawn in a legion of new followers through his spiritual teachings and bestselling books like “The Art of Happiness.” He has even won a Nobel Peace Prize.

Yet Tibet has moved no closer to independence — and it appears to be losing ground in its struggle.

The recent thaw in traditionally frosty relations between China and India — where the Dalai Lama has lived since 1959 — spells trouble for the future of Tibet. As the two Asian giants warm up to each other, it is more likely that the issue of Tibet will recede further into the background. Coupled with China’s continued efforts to remake Tibet in its own image, prospects for independence appear dim.

Known as the “rooftop of the world” for its awesome mountains and breathtaking valleys, Tibet for centuries had been an independent state that enjoyed an equal relationship with China. But in 1950, shortly after the rise of communist China, the Chinese army invaded Tibet.

The following year, Tibet signed an agreement for nominal autonomy — for all practical purposes bringing the region under Beijing’s control. In the ensuing years, China clamped down further on Tibet. In 1959, Tibetans staged a revolt but were crushed by the Chinese army. In the aftermath, the Dalai Lama fled to India — along with 80,000 Tibetans. They were granted political asylum, and it was there, in Dharamsala, that the Dalai Lama helped found the Tibetan government in exile.

Beacon for peace

During his life in exile, the Dalai Lama has grown from a young monk in his 20s into one of the world’s most compelling voices for peace. The tradition of the Dalai Lama as the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet goes back centuries. Followers believe there is one dalai lama who is reincarnated; when a dalai lama dies, monks set out to find his successor. India has been the most ardent supporter of the current Dalai Lama, allowing him to form the government in exile on its soil.

Nevertheless, India has also had to balance its own economic, territorial and military interests in the face of a powerful Asian neighbor separated by Tibet. India’s bitter memories of a humiliating defeat by China in 1962 have long lost their intensity. And the two countries have lately attempted to put their relations on an even keel, driven mainly by economics. As the world’s most populous countries, they recognize the importance of maintaining peace as they seek to be the pre-eminent powers in Asia.

A series of recent events, starting with the Indian prime minister’s visit to China in June, may jeopardize Tibet’s struggle for independence. During Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s visit, India reiterated its recognition of the Tibetan Autonomous Region as a part of the People’s Republic of China. On its own, that recognition would not have been considered significant. But China reciprocated by accepting the northeastern region of Sikkim as a part of India, though Sikkim has been a part of India since 1975.

Bargaining chip

As long as India and China held to their stubborn positions on territorial disputes along their long shared border, there was a chance that New Delhi could use the Dalai Lama as leverage simply because of his presence there. Now that the two adversaries have begun to talk about disputed territories of about 12,700 square miles along India’s northwestern border with China, chances are the Dalai Lama’s presence would no longer be seen as a bargaining chip.

In another sign of cooperation, India and China concluded their first joint military naval exercises in November. This was followed by the first-ever visit of a high-level Indian army delegation to Tibet. The symbolic visit signaled that both sides are willing to let bygones be bygones.

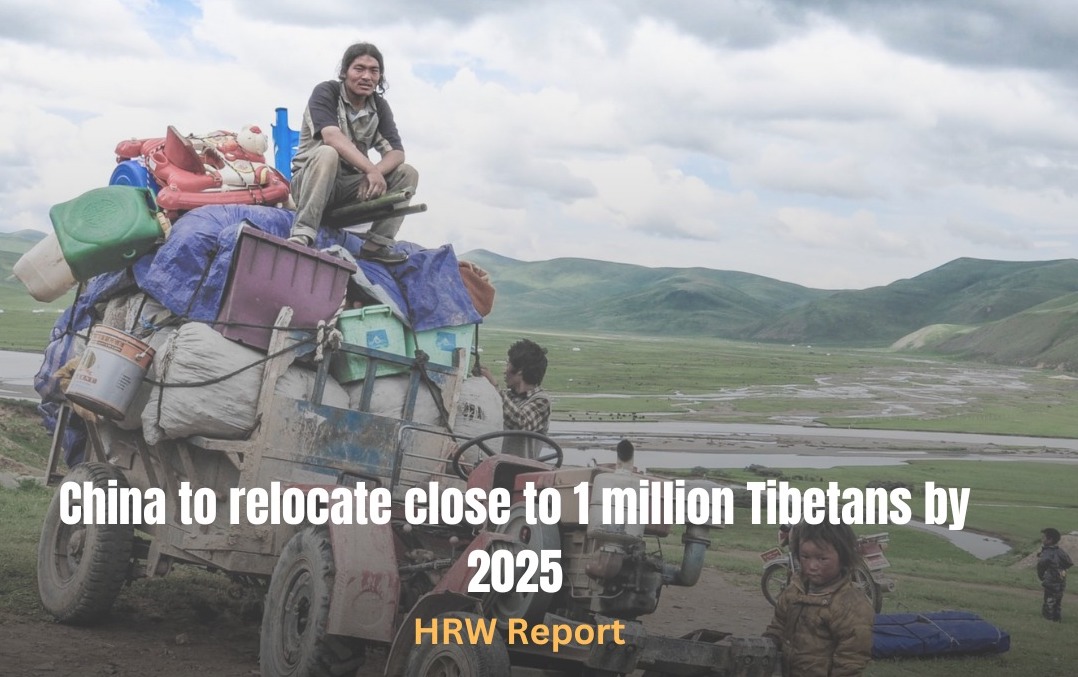

Meanwhile, China has fashioned the region in its own image, including altering Tibet’s demographics by moving Han Chinese people into Tibet. According to estimates, Tibet now is home to about 6 million indigenous Tibetans and 7 million Han Chinese.

Beijing is also strengthening its hold over Tibet through economic activities. An example is the construction of a railroad linking mainland China and the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, which is bound to make it easier to bring in military and civilians. Tibet constitutes one-quarter of China’s territory and is rich in minerals, making it tough for Beijing to let go.

Given these geopolitical forces, the only viable option Tibetans have is precisely defined autonomy within China, ensuring a self-rule and unambiguously stating what areas of government the Tibetans would control. Contentious areas would involve nearly every major issue, from judicial and legislative powers to cultural and religious affairs.

Experts are looking at several models of autonomy, including the “one country, two systems” model followed by China in Hong Kong. China’s quest for economic growth and geopolitical clout will compel it to contain, if not eliminate, conflicts within its territory. Tibet is potentially the most troublesome because of the Dalai Lama’s powerful advocacy of the right to self-rule.

The Dalai Lama has consistently said that “any relationship between Tibet and China will have to be based on the principle of equality, respect, trust and mutual benefit.”

“It will also have to be based on the principle which the wise rulers of Tibet and China laid down in a treaty in 823 AD,” said the Dalai Lama in an interview. “This treaty still remains carved on the pillar that stands in front of Jokhang,” Tibet’s holiest shrine. The treaty reads: “Tibetans will live happily in the great land of Tibet, and the Chinese will live happily in the great land of China.”

The middle path

During his early years in exile, the Dalai Lama favored independence. But in the past 15 years, he has come to recognize its impracticability. He knows his options are limited because of China’s stranglehold over Tibetan affairs, and the world’s waning attention. Recently, he has been advocating the middle-path philosophy. While this would guarantee that Tibet would retain its distinct political, social, cultural, religious, economic and linguistic identity, it also means abandoning the idea of complete independence from China.

As time goes by, the Buddhist master’s negotiating space is getting narrower. Chinese and Tibetan scholars have even suggested that Beijing may be waging a war of attrition against the Dalai Lama, waiting for his demise. The thinking behind this cynical strategy is that the next young boy to be named dalai lama would naturally take a long time to rise to a position of influence.

Already, though, there are signs of defiance among young Tibetan exiles in India who are openly advocating that Tibet secede from China rather than settle for autonomy. The Tibetan Youth Congress, which claims 20,000 members worldwide, has said it does not support the Dalai Lama’s middle-path philosophy.

But with no solution in sight, the Dalai Lama’s only choice is to craft a compromise for autonomy, however unpopular with the younger generation of Tibetans.

MAYANK CHHAYA is an Indian journalist who recently completed the only authorized biography of the Dalai Lama. He wrote this article for Perspective