Albuquerque Journal

LATIR RANCH, N.M. – Up on a grassy platter of ground midway between Taos and the Colorado border, more than 100 shaggy head of yak stand in a bunch, warm under their wool in a hard morning wind.

The fuzzy beasts from the Himalayas look right at home here.

The fuzzy beasts from the Himalayas look right at home here.

Blanca, Crestone and Culebra peaks – all jagged 14,000-footers – loom to the north, topped with snow.

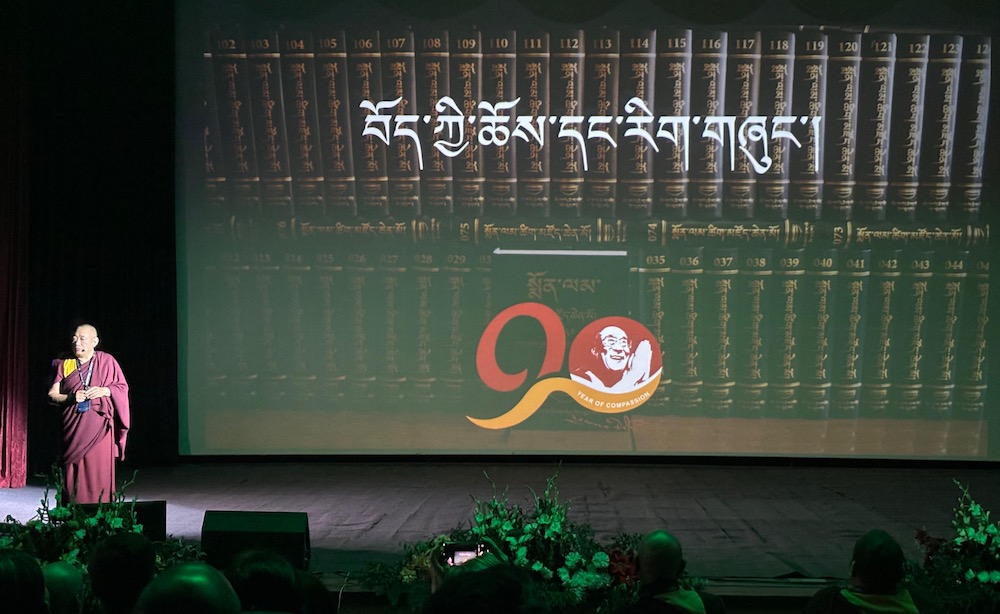

And to the south stands a Tibetan Buddhist stupa, its gold adornments glinting in the sun.

What are yak – 5,000-year natives of Tibet and Nepal – doing here in the cattle and sheep country of the American West?

They’re offering a lower-in-cholesterol alternative to beef, a cashmere-like wool and a head-turning double take for motorists heading north toward Colorado.

“They’re sure different,” said Chuck Kuchta, a fifth-generation cattle rancher from Clovis who, as manager of the Latir Mountain Ranch, is the man responsible for one of the largest yak herds in the country.

Kuchta likes to call the yak “Taos hippie cows” and, sure enough, they bear some shaggy resemblance.

Kuchta, 29, said goodbye to cattle and took the job as a yak herdsman not because he has any beef with cattle. He just had an open mind to a different kind of livestock.

Rancher is no ‘yakboy’

But don’t call the former cowboy a “yakboy.”

But don’t call the former cowboy a “yakboy.”

“I’ve heard ‘yakalero’ and I kind of like that,” Kuchta said.

Kuchta manages the 6,500-acre Latir Mountain Ranch for Tom Worrell Jr., who has added yak to his growing portfolio of environmentally conscious and slightly oddball undertakings around Taos.

Worrell’s wealth came from a chain of weekly newspapers that he sold in 1995. He came to Taos in the mid 1990s and stayed, and he has used his fortune to fund something of a personal renovation of the little town.

Worrell has bought and renovated about two dozen buildings in Taos, started a school and built a luxury 36-suite boutique hotel that features its own natural water recycling system and stunning architecture and art.

To his impressive collections of contemporary art and adobe buildings, Worrell has added yak.

He got turned on to the sturdy oxen about six years ago when the monks from the Tibetan stupa down the road from the Latir ranch complained they couldn’t find any yak meat.

“I started researching them and I said, ‘This is a perfect place for them,’ ” Worrell said.

Soon he ordered 40 from a breeder in Idaho and yak quickly replaced buffalo on the ranch.

In the process, Worrell became enamored.

“They’re just magnificent,” he said. “I love them. They’re just beautiful animals.”

There are only a couple thousand yak being raised in the United States, and the New Mexico herd, at 138 head, is the third largest. It is also the only certified organic herd.

Kuchta has shown the animals at the famed Denver livestock show and he sells bulls, cows and calves to others interested in building a herd.

Average price of a yak: about $2,500. A top quality bull can cost $5,000.

Kuchta and others pen the yak each spring and painstakingly pull the animals’ molting wool off by the handful. It is a fine and soft wool that sells to weavers for about $16 an ounce.

And the ranch butchers a yak each month.

The meat goes to the kitchen at El Monte Sagrado, Worrell’s Taos resort, and another resort he owns in Florida. The lamas also get a share.

In Taos, chef Kevin Kapalka serves rare yak steaks and yak cheeseburgers as well as ground yak in a variety of creative dishes: yak egg rolls, yak ravioli, yak chili, yak dumplings and yak meatballs.

Kapalka, a Culinary Institute of America grad who has worked at luxury resorts around the world, is delighted by the challenge of cooking yak.

“It’s unique,” Kapalka said. “As a chef, you’re always looking for a product nobody else has.”

It is a lean meat, about 5 percent fat compared to 15 percent fat in beef. People say it tastes like buffalo but milder.

Yak like the high mountains here, and the mountains would probably agree they are a good fit. They don’t need much water; they eat about one-third what cattle do; they happily climb rocky mountainsides; they’re resistant to diseases; and they calve without much bother.

And they are hardy.

Stragglers survive in winter

Last fall, Kuchta and the other herdsmen could not find three stragglers during the roundup and so they left them in the mountains to survive deep snow drifts and temperatures of 30 degrees below zero.

Come spring, the three happy and healthy yak picked their way down the mountainside to join the rest of the herd.

“They’re tough,” said Kuchta. “And they’re fast. They can show an elk a thing or two about running through the woods.”

One of the most pointed differences between yak and their domesticated bovine cousins is their horns.

They grow fast and they grow long. A full-grown male’s horns can extend three feet on each side and be thick as a baseball bat at the head.

Kuchta has learned not to stick around when an angry yak lowers its head.

“They’ve counted the change in my back pocket, for sure,” he said.