Gautam Adhikari

WASHINGTON: To borrow a line from the nuns in that old musical, how do you solve a problem like China? It isn’t a will o’ the wisp that’ll go away; it isn’t a clown, though it might think the rest of us are. It is a worry for the world and a headache for India.

The Economist, which is now a weekly must-read for trend analysts everywhere, ran a special survey recently on ‘The Dangers of a Rising China’. Several Asia-watchers have written volumes full of anxiety. One by Martin Jacques, titled ‘When China Rules the World’, declares in its subtitle: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order. China’s influence, says Jacques, will extend well beyond the economic sphere. It will have social, cultural and political repercussions.

Chinese leaders talk of its “peaceful rise”. On the surface, it would seem so. China doesn’t have naked colonial aspirations like erstwhile imperial powers, it generally works through multinational groupings, not unilaterally, in world affairs, and it has gone out of its way to settle border disputes with many neighbours. Still, it houses 20 per cent of the human race, will soon become the world’s largest economy and maintains the biggest standing army of any nation. And it is ultra-nationalistic.

A prickly nationalism has replaced communism as the driving ideology of the party-controlled Chinese state. It has indeed settled several border disputes; yet, when it deals with, for instance, Japan or India it bares its teeth over territorial claims. It skirmishes with Japan on the seas. It demands chunks of Indian territory and makes whimsically aggressive gestures over granting visas to Indians.

Its almost hysterical reaction to the award of a Nobel peace prize to Liu Xiaobo, an imprisoned dissident, is an example of a disturbing paranoia. Instead of brushing off the award as something that mattered little, it snarled through an official organ that the members of the Nobel committee were a bunch of “clowns”. In fact, that would be an apt description of the pathetic bunch of 18 or so dictatorships and eccentric nations that it rounded up to boycott the award.

As leader of the world’s largest democracy, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh absolutely the right thing in ignoring Beijing’s demand that India join that motley bunch. China’s supporters and a few intellectually geriatric souls may spy sinister motive in India’s refusal to join the boycott, but the best motive of all is democracy itself. It is high time that New Delhi abandoned being apologetic to anti-democratic clowns. Its democracy has flaws, as all democracies do since they can only approximate an ideal that by definition is a set of feasible compromises, but it is a model that one day might rival China’s as a beacon of growth and sustainable prosperity.

Although it may appear laughable in current circumstances, a contest of ideals in the future, perhaps beginning as early as a decade from now, is likely between India and China. They will each be a billion and a half strong, they will be two of the world’s three largest economies and, unless either changes radically, they will showcase competing models of sustainable growth vying for appeal among other growing economies. If it can get its act together to sustain high growth, India’s democratic alternative to China’s authoritarianism can prove to be the better option.

By that time, the spell of China enjoying a demographic dividend will end. India will expand its youth bulge which will make its average age 29 against China’s 37 in 2020. India will have more productive workers of an active age than China, which will bear an economic and social burden of age while India’s productivity will rise.

China’s growth will slow by 2015 when India’s rate is expected to surpass it, says the World Bank. And there are signs, say investment bankers, that in 10 to 15 years’ time India’s economic potential may turn out better than China’s.

We tend to blame democracy for our comparatively poor performance but India has in recent years had high growth with democracy. Forty years of wrong economic policies were more to blame for lacklustre performance than free elections or a free media. Free speech allows an escape for pent-up frustrations. China allows few valves for releasing popular emotions even as it witnesses, according to several reports, around 90,000 spontaneous protests every year. When an expanding middle class demands more in the open market and if galloping inflation hits hard thanks to policy errors or unforeseen global conditions, can China’s model survive?

No doubt, India hardly performs at optimal efficiency. Uneven growth, weak governance, poor hygiene and persisting mass poverty continue to hamper our quest for prosperity. But democracy is not to blame for managerial ineptitude, as the relatively strong performance of several states in the north, west and south shows. Even Bihar has demonstrated signs of growth with good governance in recent years. Actually, democracy helps hold this hugely diverse nation together by allowing a plurality of views to compete with one another. It seems messy but it works better.

In short, democracy is the best selling proposition of Brand India. When the enraged dragon breathes fire, roar right back. Let’s stop being chicken. Instead, be the tiger we say we are.

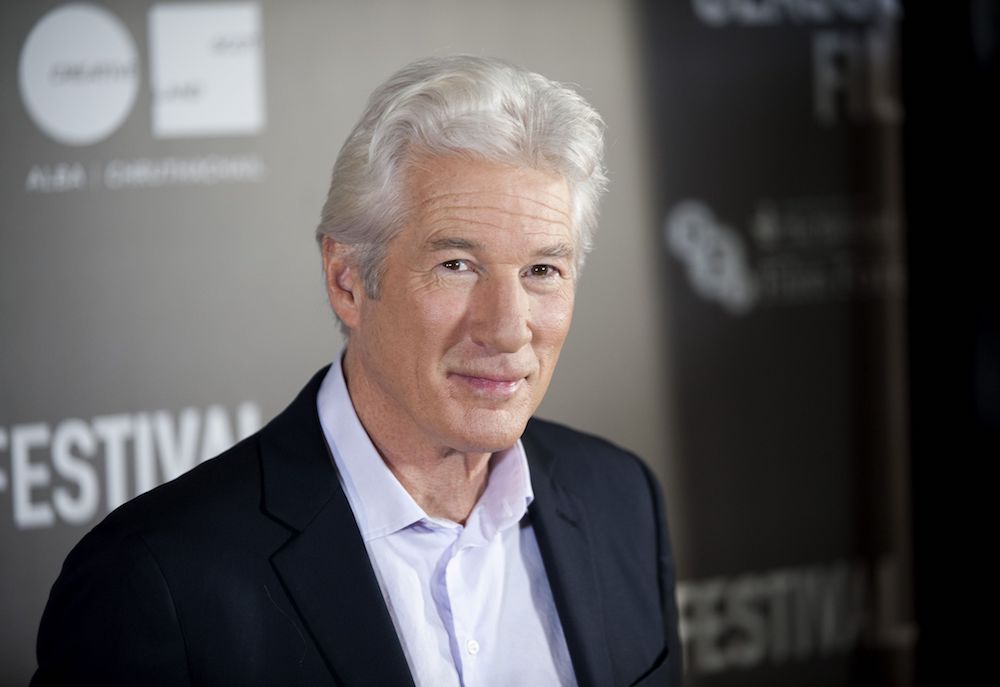

The writer is a FICCI-EWC fellow at East West Centre in Washington DC.