Even second and third generation Tibetans are keen to return to their country, refusing citizenship

Bangalore: “I love Bangalore, we love India, but our roots are in Tibet and we will go back some day,” says Tenzing, a young shopkeeper at the Tibetan market on Rest House Road, echoing perhaps the sentiments of around 85,000 Tibetan refugees in India. Bangalore itself is home to around 500 Tibetan families.

Bangalore: “I love Bangalore, we love India, but our roots are in Tibet and we will go back some day,” says Tenzing, a young shopkeeper at the Tibetan market on Rest House Road, echoing perhaps the sentiments of around 85,000 Tibetan refugees in India. Bangalore itself is home to around 500 Tibetan families.

When in 1962, the State Government announced the allotment of land for Tibetan refugees in Karwar, Mysore, and Chamarajanagar districts, there was large-scale migration from Tibet and the northeastern States where Tibetans were mostly employed in road construction and repair work. With minimal or no formal education, they settled in Karnataka. Many of them started garment businesses and selling sweaters on pavements near Majestic. Some others moved to Bangalore in search of better opportunities.

Red tape

Many second and third generation Tibetans now work in beauty parlours, restaurants and call centres in the city. Being refugees, the red tape involved in enrolling in professional courses and donations has discouraged the Tibetan youth from pursuing higher education.

Though all refugees who were born here or have lived here for more than 14 years are eligible to apply for Indian citizenship, and the advantages that come with it are significant, only 2 per cent to 3 per cent have chosen to do so. Refugees have no ownership rights, no permanent address or other such details to fill in the numerous spaces of bureaucratic paperwork.

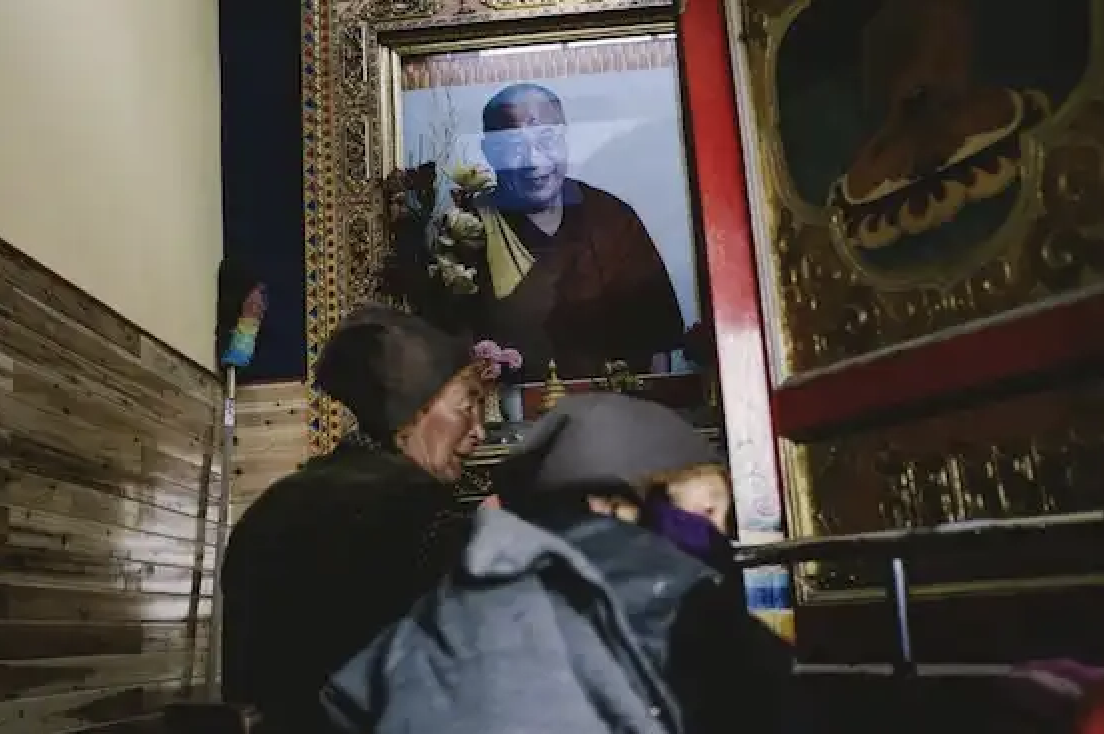

Though there is a lot of interaction between Tibetan and Indian youth, homogenous groups are more common. Rinzing, a graduate from Miranda House, Delhi, says that while she got along with most Indians, her closest friends were always Tibetans. They accept and adapt to the confluence of cultures but their root identity remains strong. Sonam, who manages the accounts at the Central Tibetan Relief Committee, Viveknagar, says that when his parents moved to India in the Sixties, they looked at it as a temporary phase. “And they have passed it on to our generation as well. Even a five-year-old child talks about wanting to go back to Tibet,” he says.

In the psyche of the second and third generation Tibetans, there is no real sense of permanence. There is always a vague feeling of inertia, a longing to go back to a country they have never seen.

Choephel Thupten, special officer at the Central Tibetan Relief Committee, says that this has had a negative effect on the community, especially for those in business.

Their cultural identity is strongly ingrained in the collective Tibetan psyche especially in heterogeneous environments. For today, the young Tibetan is as comfortable in a chuba as she is in a kurta and they feel completely at ease in Bangalore, their adopted home.