By Ajaz Ashraf

It is conceivable a Tibetan could in the near future again set his or her body on fire. It is also possible to imagine what the response to such an act would be – frenzied, doleful coverage of the incident by the media, a crescendo of criticism against Beijing’s suppression of a people, and prominent voices demanding that the Dalai Lama issue a statement condemning self-immolation as a form of protest. You can only hope and pray the world won’t have to countenance the horror.

Yet, it is an idea which is perhaps incubating in the Tibetan Diaspora, deeply frustrated as they must be at the world’s indifference to the self-immolations of their brethren in their homeland, ruthlessly oppressed and peremptorily partitioned and amalgamated with different provinces of China.

India is no exception to this silence. No prominent leader, not even from the Opposition, nor even the palpably anti-China media of India – ordinarily quick to seize upon a hint of Chinese arrogance or bellicosity – has been unduly bothered by the rising number of Tibetans setting themselves on fire. We were not even shaken into analysing the phenomenon of self-immolations in Tibet as it breached a depressingly significant mark.

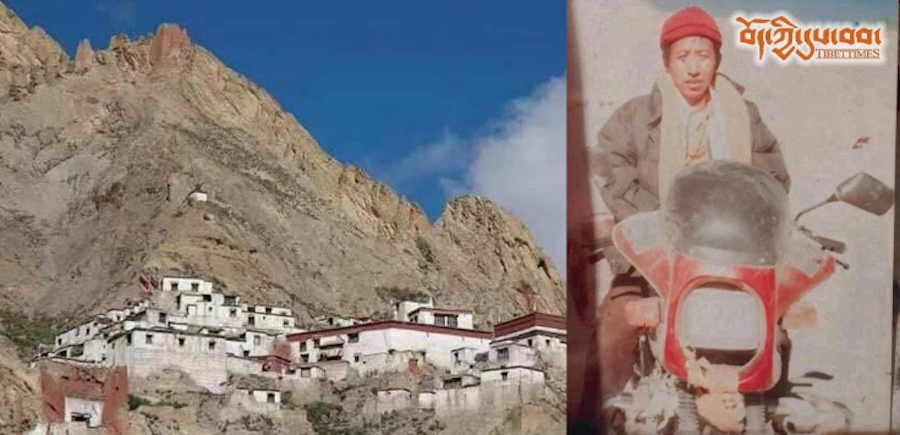

On 3 February, Lobsang Namgyal became the 100th Tibetan to commit self-immolation since 27 February 2009, the day on which Tapey became the first to set his body ablaze and triggered an initial sense of concern. The current count stands as follows: 104 self-immolations and 87 dead; the whereabouts of those who were burnt badly but survived are not known. From the solitary self-immolation of Tapey in 2009, the figure rose to 12 in 2011, to 83 in 2012; and five have already burnt themselves to death this year. It’s an overwhelmingly a movement of the young – 77 of the 102 self-immolators were between 15 and 29 years old.

We in the Indian media have our gaze trained towards the West. We diligently report every survey rating the American President’s performance; we fill our pages every time a crazed American fires on schoolchildren or breathlessly follow the sexual escapades of every wannabe actor. Our interest in the neighbourhood is confined to measuring the several inches by which Pakistan sinks into a political morass every time a bomb explodes in a crowded urban mart.

Yet, we blithely ignore the Tibetans who set themselves on fire, hurting nobody but themselves in the hope their embrace of a fiery death could turn the attention of the world to their plight. Our indifference to the self-immolations in Tibet could prompt them to display to us in our cities the ordeal it is to burn to death. Twenty-five-year-old Duptse, a Tibetan, became the harbinger of the grim future awaiting us as he turned himself into a raging ball of fire in Kathmandu last week. In March last year, Delhi suffered the same mortification.

It seems inevitable and logical for Tibetans to seek more spectacular settings for self-immolation, for their unique form of protest not only seeks to defy Chinese rule but to also persuade through their suffering an indifferent world of the need to mount pressure on Beijing to grant them their cultural and religious rights. (They relinquished their demand for an independent homeland a while ago.)

These twin messages of defiance and a cry for support constitute the meaning of almost every Tibetan self-immolation, invariably carried out outside famous monasteries or public places, thus providing the opportunity for capturing on camera or video the horror of their burning to death. No doubt, the downloading of these ghastly scenes on the internet suggests a network of activists hoping to exploit self-immolations for garnering support for the Tibetan cause.

Similarly, messages some self-immolators recorded before walking to their chosen site of death have been widely disseminated. Almost all such messages sang paeans to the Dalai Lama or harped on the need to maintain the cultural purity of the Tibetan people.

Beijing has grasped the message of defiance implicit in the self-immolations, evident in its decision to flood Tibetan towns with troops, the harsh crackdown which follows every suicide by burning, and the lengthy imprisonment recently awarded to a few. Yet, through the cracks in the security cordon a Tibetan slips out now and then, douses himself in inflammable liquid and becomes a searing ball of fire.

But such defiance, Tibetans know, will not acquire a salience until the international community is repulsed into overlooking the economic underpinnings of its relations with China to cry out, ‘Enough!’ Might it not then occur to the Tibetans to carry directly their message of self-immolations to the cities in the West, much in the way Islamic suicide bombers did with their horrific methods?

Indeed, the self-immolator’s psychology closely resembles the suicide bomber’s – except in one crucial way. The self-immolator harms no one but himself; the suicide-bomber wants to kill as well as be killed.

However, both believe death is the only recourse left for them to secure justice. Both choose to die because they wish through their sacrifice to provide a better future for their people. Yet, what distinguishes the suicide bomber from what cultural theorist Terry Eagleton calls the martyr, or the person who fasts to death for a cause or demand, is that the latter, as noted above, doesn’t injure or kill others.

In a piece for The Guardian in 2005, Eagleton wrote, “The martyr bets his life on a future of justice and freedom; the suicide bomber bets your life on it. But both believe that a life is only worth living if it contains something worth dying for.” Indeed, the self-immolator fits the description of Eagleton’s martyr.

Considering the sharp escalation in self-immolation in Tibet, it seems there is an inexhaustible supply of men waiting to court death, just as the earlier generation of suicide bombers spawned more deadly imitators.

The only question is: given the apathetic response of the world to their plight and Beijing’s refusal to listen to their key demands, is it not possible for the potential self-immolator to reinterpret the Tibetan Buddhism creed of non-violence much the way the Koranic injunction against suicide was?

The author is a Delhi-based journalist and can be reached at ashrafajaz3@gmail.com. Article submitted by the author and re-published with permission from Firstpost.com.

[OPINION-DISCLAIMER]