By Sheri Linden

PALM SPRINGS — The subtitle of new film “The Sun Behind the Clouds” — “Tibet’s Struggle for Freedom” — refers not only to the half-century dispute between Tibet and China but also to the divisions that have arisen among Tibetans around their beloved leader. The film is essential viewing for anyone who cares about the fate of the mountain region and the legacy of the Dalai Lama.

PALM SPRINGS — The subtitle of new film “The Sun Behind the Clouds” — “Tibet’s Struggle for Freedom” — refers not only to the half-century dispute between Tibet and China but also to the divisions that have arisen among Tibetans around their beloved leader. The film is essential viewing for anyone who cares about the fate of the mountain region and the legacy of the Dalai Lama.

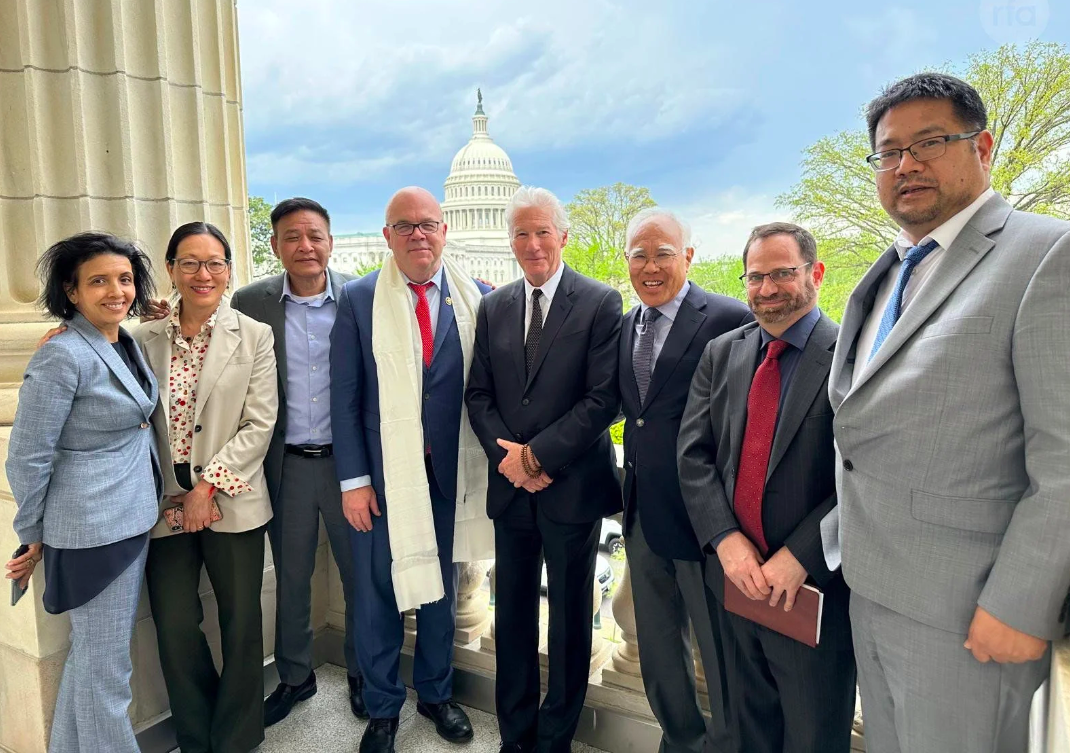

The documentary’s North American premiere at the Palm Springs International Film Festival received a bit of a publicity boost after Chinese film authorities requested its screenings be canceled and, in protest of the fest’s refusal to do so, withdrew two Chinese movies from the lineup. But regardless of attempted power plays against it, the film is notable for its focus on an extraordinary year in Tibet’s history and on Tibetans themselves — historians, writers, activists, all eloquent, impassioned and living in exile. Chief among those exiles is the 14th Dalai Lama, 74-year-old Tenzin Gyatso, who granted the filmmakers considerable access. He’s seen in prayer, in new interviews and in his world travels as ambassador of peace.

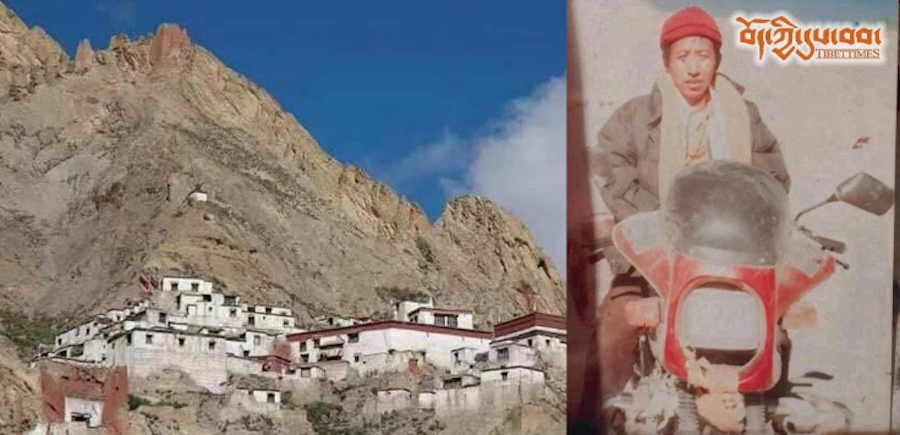

Co-directors Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam have been making films about Tibet for 20 years. The latter, who also narrates “Clouds,” is himself a first-generation exile, born in 1959, the year of the failed uprising against the occupying Chinese and the beginning of the Dalai Lama’s India-based government-in-exile. In 2008, the filmmaking pair hurried to catch up with a number of dramatic events: worldwide protests centering on China’s vaunted “coming-out party” to the world as host of the Olympics and, more significant, the biggest uprisings in Tibet since 1959.

The doc’s talking heads make clear that the Dalai Lama’s position as a spiritual leader who also is a political figure creates a profound dilemma for him and his people. They’re incompatible roles, some argue, and the leader himself indicates he wouldn’t disagree with that assessment. Discussing his Middle Way — the compromise policy he adopted in the late 1980s that forsakes the fight for political independence while insisting on meaningful cultural autonomy — his eyes betray a deep sorrow. Not only does his proposal continue to be rebuffed and misrepresented by the Chinese government, but it has done nothing to lessen his people’s pain.

In the urgent context of the battle to save an endangered way of life from what one commentator calls China’s “imperialist cultural invasion,” the effectiveness of the Dalai Lama’s high-profile visits with world leaders is debatable. The film shows him laughing with Prince Charles, addressing the German parliament, speaking with Chinese journalists in Seattle. However potent he is as a symbol, many activists interviewed for the film believe he could put that symbolism to better use. Some would have preferred, for example, that he had joined the 2008 march to Tibet through India, a months-long protest against China that the filmmakers track quite affectingly.

As with any protracted struggle for human rights, the tension between ideals and political reality is not easily resolved. There’s an undeniable pragmatism to the Tibetan leader’s approach; China, he says, can provide the economic development Tibet so desperately needs. But those who remain committed to independence, particularly younger Tibetans, see his notion of global interdependence, however essential to Buddhist philosophy, as out of touch.

The well-crafted film benefits from the understated lament of Oscar winner Gustavo Santaolalla’s score. But the main melody here is the voices of the Tibetan people. Whether the Dalai Lama will leave them in a better position remains unclear. But when Chinese authorities are still trying to silence filmmakers, there’s no doubting his wisdom when he notes that China is “powerful but lacking in self-confidence.”

[OPINION-DISCLAIMER]