By ELEANOR HERER

You won’t find McDonald’s in Lhasa, but you can order a yak burger on a sesame bun at the Hard Yak Café. Even the french fries are crisp. Should you prefer Tibetan dining, try the Himalayan Restaurant across the hall.

In Lhasa, the heart of Tibet, the traditional and the contemporary dwell side by side. After five decades of occupation and modernization, the capital city thrives as a city of contrast.

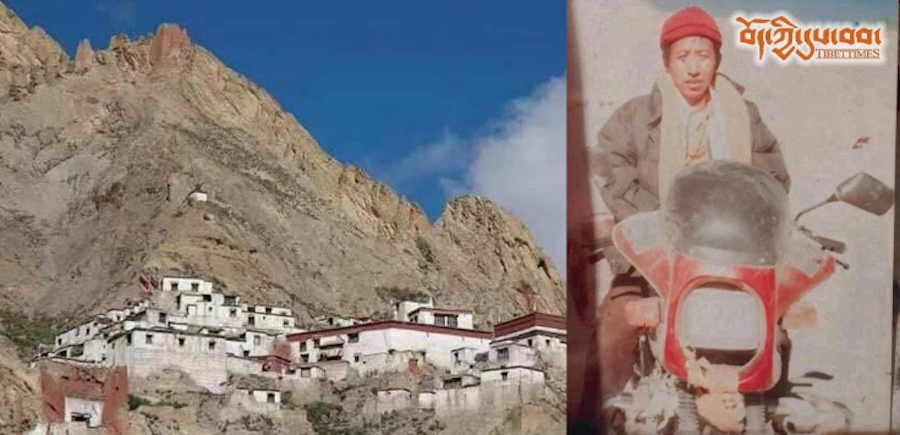

Ancient palaces and temples rise around the corner from modern box-like concrete buildings. The green-top taxicab stops to let a small group of nomad pilgrims with their goats cross the main street. Two apron-clad village women pause the repetitions of their mantras and the whirling of their prayer wheels just long enough to watch the ballet sequence broadcast on a television in the store window.

The Lhasa I recently visited is a divided city. In the old city, the Tibetan sector, I saw narrow streets dotted with temples and friendly faces that smiled to greet me as I passed. In Chinatown, the western section of the city, I walked with shoppers hurrying along the wide avenues lined with boutiques, offices and restaurants. The glass and concrete buildings of Chinese architecture stood out next to the traditional Tibetan buildings of large stone walls and wooden-framed windows.

Since its beginnings in the 7th century, Lhasa has reflected the country’s power and political changes. Population has increased more than five-fold since the occupation, mostly Han Chinese migrants who set up shops and restaurants and run the taxis.

According to the people I spoke with, there is little socialization between the two peoples. The Tibetans regard the Chinese as rude and money-hungry; the Chinese regard the Tibetans as lazy and superstitious.

Officially a bilingual city, Chinese characters proclaim the names of stores with the Tibetan script written in smaller letters underneath. Children learn both languages, although parents worry that most of the “fun” and “interesting activities” are in Chinese and that the new generations must be fluent in Chinese to have gainful employment.

When I remarked about the many pool tables on the sidewalks around the old city, I was told, “Tibetans have plenty of time to play pool.” Many lost jobs to the Chinese, who get preferential treatment to encourage them to stay.

Yet since 1980, the government has undertaken massive construction projects, building sewer systems and wide highways. Modern street lamps line the broad main avenues, and at night, colourful lampposts sparkle like fireworks. I was able to phone home as easily as in any large city, and was even able to catch up on e-mail, slow but available. As part of the major restoration of religious sites destroyed during the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese poured $7 million into restoring the Potala Palace, “museum-style.”

While hundreds of pilgrims arrived at the Potala to perform their devotions, we tourists trailed through the chapels and temples admiring the statues and golden thrones. More than once, the silence in the sacred rooms was shattered by a ringing cell phone attached to a Chinese tourist’s belt.

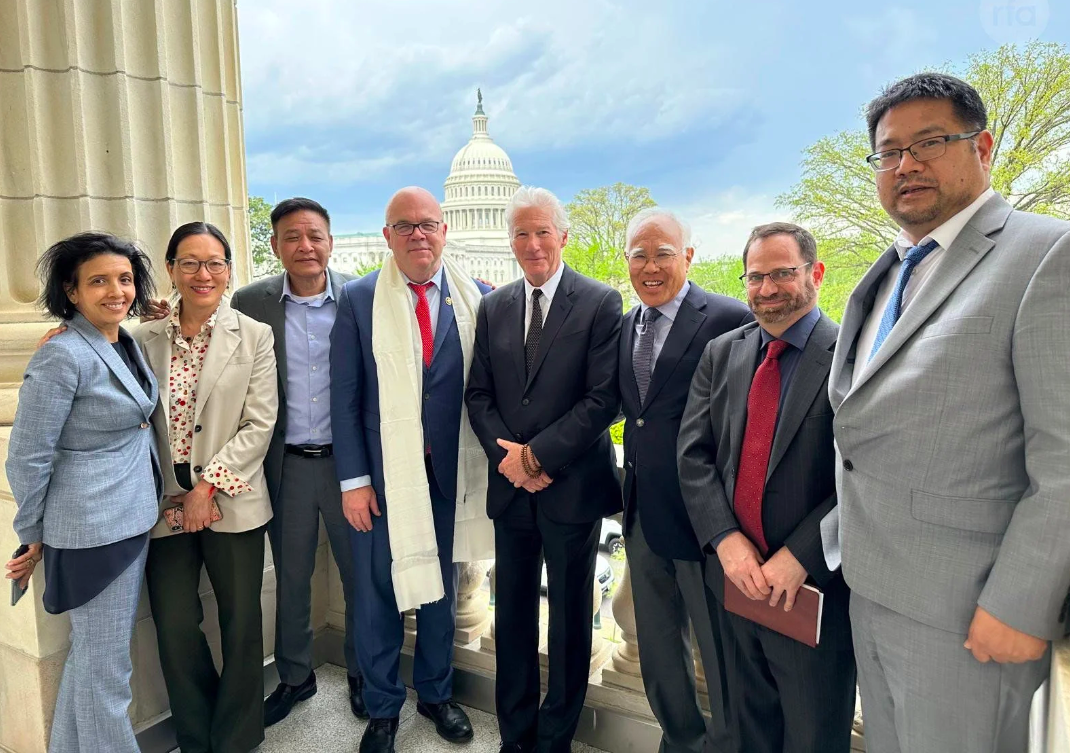

As everyone who takes a guided tour knows, there’s always a group photo; ours was taken in the large open area in front of the Potala. This area was one of the oldest districts in Lhasa until recent years when it was razed to create Potala Square.

Paved with grey stone slabs and neon lights, the huge plaza reminds one of Tiananmen Square in Beijing. At the far end, a new monument commemorates the “peaceful liberation” of Tibet. Yet, today, the palace remains the symbol of Tibet and its hope for the return of the Dalai Lama.

Strolling in the medieval atmosphere of the Barkhor Market, you experience a sense of the old Tibet. In the modern downtown area, you feel as though you’re in a modern big city in China.

And in both sectors, in restaurants and cafés, you can order Lhasa “Beer from the Roof of the World” with a logo of the Potala on the label.