Tenzin Topdhen

Abstract

Northeast India, geographically isolated and connected to the mainland by the tenuous Siliguri Corridor, faces a formidable challenge from the deepening strategic nexus between China and Pakistan. This article analyzes the collusive threat posed by this “iron brotherhood,” examining how Beijing and Islamabad coordinate to exploit internal vulnerabilities in India’s Northeast to stretch Indian military resources and undermine regional stability. Drawing upon geopolitical analysis, the paper argues that the conventional approach of managing the border is insufficient. Instead, it posits that the unresolved status of Tibet is the fulcrum of regional instability. The article concludes that actively supporting genuine autonomy or self-determination for Tibet is not merely a moral imperative for India, but a supreme strategic necessity that could act as the ultimate “game changer,” neutralizing the northern threat and dismantling the efficiency of the China-Pakistan axis.

1. Introduction: The Geopolitics of Vulnerability

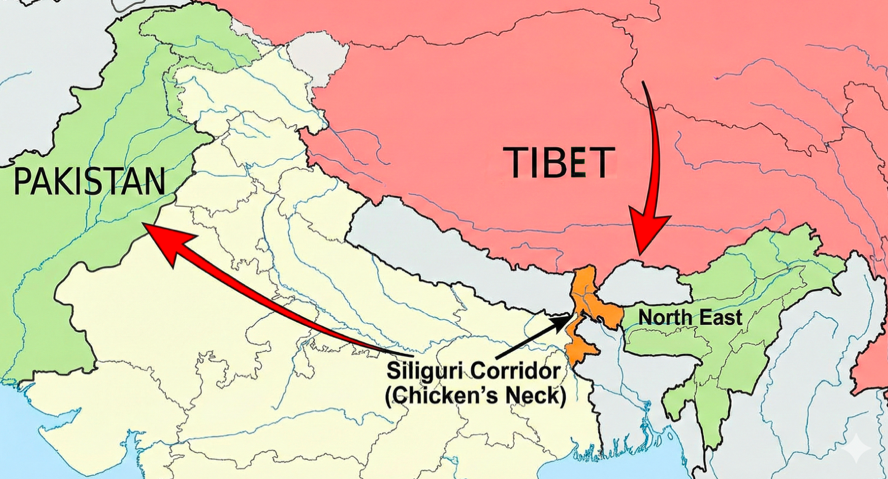

The Northeastern Region (NER) of India is a unique geopolitical entity. Sharing over 4,500 kilometers of international borders with China, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, it is linked to the Indian heartland by the Siliguri Corridor—a narrow strip of land barely 22 kilometers wide at its narrowest point, often referred to as the “Chicken’s Neck.”

For India’s adversaries, this geography presents a significant tactical opportunity. The region has historically battled insurgencies fueled by ethnic fault lines and underdevelopment. However, in recent decades, local grievances have been amplified by external interference. The convergence of strategic interests between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has created a synchronized threat perception for India, with the NER increasingly becoming a theater for this proxy maneuvering.

While New Delhi has traditionally viewed the threats from its western (Pakistan) and northern (China) borders as distinct, albeit related, the current strategic environment demands viewing them as a cohesive, collaborative front. Central to countering this pincer movement is the often-overlooked factor of Tibet, whose forced annexation by China in the 1950s erased the historical buffer between India and the East Asian behemoth.

2. Anatomy of the China-Pakistan Nexus in the Northeast

The collaboration between China and Pakistan regarding India’s Northeast is not merely a coincidence of interests but a structured aspect of their “All-Weather Strategic Cooperative Partnership.”

2.1 China’s Strategic Drivers

China’s primary objective in the NER is territorial and strategic. It claims nearly the entire state of Arunachal Pradesh as “South Tibet” (Zangnan), a claim it periodically reinforces through “renaming” locations and aggressive patrolling[1]. By keeping the border disputed and unstable, China forces India to commit substantial military resources to the region, diverting attention from Chinese maritime expansion in the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, control over the NER flank secures China’s hold over Tibet and facilitates its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) ambitions into Southeast Asia.

This strategy is not limited to cartographic aggression but manifests in real-world harassment of Indian citizens, constituting significant diplomatic setbacks for New Delhi. China systematically denies normal visas to residents of Arunachal Pradesh, issuing “stapled visas” instead to imply they are Chinese subjects.

A disturbing recent incident highlights this psychological warfare. According to reports, an Indian woman from Arunachal Pradesh traveling through Shanghai was harassed by Chinese immigration officials. They questioned the legitimacy of her Indian passport, asserting that Arunachal is Chinese territory and implying she should possess Chinese documentation. Such incidents are designed to demoralize the population of the border state and challenge India’s sovereignty at a personal, citizen level [2]. This persistent denial of Indian sovereignty over Arunachal remains a major friction point and a strategic vulnerability.

2.2 Pakistan’s Asymmetric Objectives and Historical Claims

Pakistan’s interest in the NER is an extension of its “bleed India with a thousand cuts” doctrine. This interest is rooted in a historical Pakistani strategic outlook, as evidenced by statements from its former leadershi

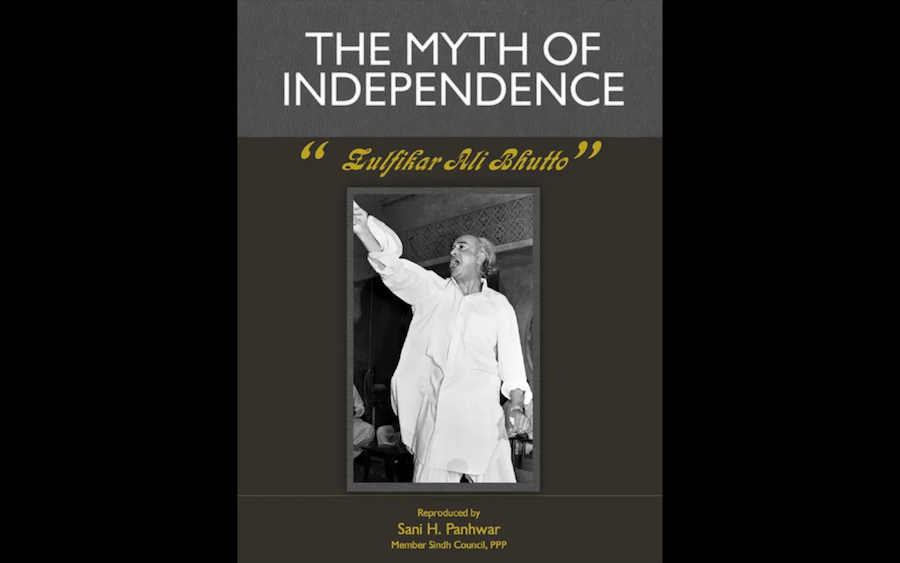

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, in his book, ‘The Myth of Independence’, laid explicit claims to the region, writing:

“One (of the problems) at least is nearly as important as the Kashmir dispute: that of Assam and some districts of India adjacent to East Pakistan. To these East Pakistan

has very good claims, (…The eviction of Indian Muslims into East Pakistan and the disputed borders of Assam and Tripura should not be forgotten.)”

Bhutto advocated a policy of ‘special relationship with non-Hindu population of Assam until this wrong (of Assam being an integral part of India) can be finally righted’.

This historical aspiration to detach Assam provides the doctrinal underpinning for Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to exploit internal fissures within the region. By supporting insurgent groups with arms, training, and financial aid—often using bases in neighboring countries like Bangladesh (historically) or Myanmar—Pakistan aims to open a second front of instability against India, stretching Indian security forces thin and distracting from the Kashmir theater [3].

2.3 Operational Convergence and Proxies

The nexus becomes operational through intelligence sharing and coordinated diplomatic and military pressure.

• Military Ties: The high-level military cooperation between the two allies is visible in events such as the visits of Pakistan Army Chiefs to the PLA headquarters.

• Insurgency and Arms Supply: The ISI has been pivotal in creating and sustaining militant groups in the Northeast. Parallel to the Muslim resistance in

Kashmir, other Islamist organisations in Northeast India were also increasingly active in the 1990s. The main militant Islamist resistance groups in Northeast India include:

o Muslim United Liberation Front of Assam (MULFA) o Muslim United Liberation Tigers of Assam (MULTA) o Islamic Liberation Army of Assam (ILAA)

o United Muslim Liberation Front of Assam

o United Reformation Protest of Assam o People’s United Liberation Front

o Muslim Volunteer Force

o Adam Sena Islamic Sevak Sangh

o Harkat-ul-Mujahideen

o Harkat-ul Jihad

Furthermore, the ISI has established reliable supply chains for weapons into the region, particularly after new supply opportunities opened up following the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia in the 1980s.

In 1991, the ISI provided weapons from Thailand to a group of 240 NSCN members. Small boats brought the cargo to Cox’s Bazaar, a port in Bangladesh, which became the hub for weapon supplies in the region.

There are credible indications of cooperation between Pakistan’s ISI and China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) regarding Indian troop movements and internal vulnerabilities[4]. Furthermore, Chinese-manufactured small arms have frequently been recovered from NE insurgent groups, hinting at a supply chain that likely involves tacit approval from Beijing or coordination via Pakistani networks.

3. The Tibet Factor: The Root of the Himalayan Crisis

To understand the threat to Northeast India, one must look beyond the McMahon Line to the Tibetan Plateau. The current geopolitical tension is a direct consequence of China’s occupation of Tibet.

Before the 1950s, Tibet served as a massive, peaceful buffer state between the Indian civilization and China. The borders were largely demilitarized. China’s annexation of Tibet brought the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) directly to India’s doorstep, transforming a peaceful frontier into one of the most militarized zones in the world.

3.1 Militarization of the Plateau

China has developed extensive dual-use infrastructure on the Tibetan plateau, including high-altitude airbases, rail networks extending close to the borders (like the Lhasa-Nyingchi railway near Arunachal Pradesh), and extensive road systems. This infrastructure allows for the rapid mobilization of troops and heavy weaponry towards the Indian border, directly threatening the Siliguri Corridor and Arunachal Pradesh[5].

3.2 Hydro-Hegemony and Water Wars

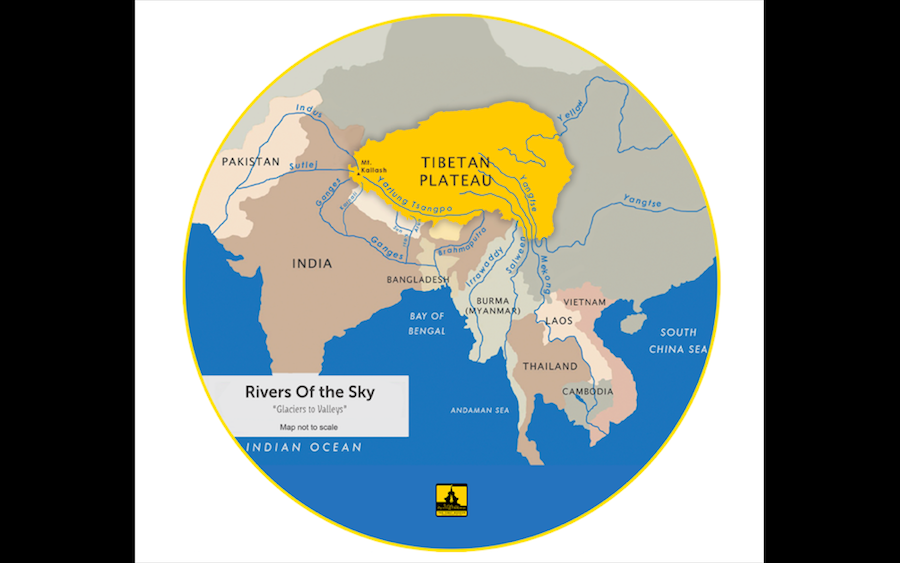

Perhaps the most critical long-term threat is the weaponization of water. Tibet is the “Water Tower of Asia,” the source of major rivers including the Brahmaputra (Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet), which is the lifeline of Northeast India and Bangladesh.

China’s frenetic dam-building program on the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra gives Beijing the ability to manipulate water flow. This creates two distinct threats: the ability to induce drought during lean seasons by withholding water, or to cause devastating flash floods by releasing excess water during monsoon seasons—a strategy already suspected in previous flooding incidents in Arunachal Pradesh and Assam[6].

4. The Strategic Game Changer: Tibet’s Genuine Autonomy

Given the depth of the China-Pakistan collusion, India’s current reactive strategy of border hardening is necessary but insufficient. A paradigm shift is required. The resolution of the Tibet issue—specifically the realization of genuine autonomy or self- determination for the Tibetan people—constitutes the single most effective strategic counter-move available to India.

Restoring Tibet’s status is not just a human rights issue; it is a critical geopolitical necessity for India’s long-term security.

4.1 Restoration of the Historical Buffer

A genuinely autonomous Tibet, governing its own internal affairs and free from the massive PLA presence, would de-escalate the Himalayan frontier. If Tibet were to regain a status similar to its historical neutrality, the immediate military threat to the Siliguri Corridor and Arunachal Pradesh would significantly diminish. The need for India to maintain massive mountain strike corps would decrease, freeing up resources for naval modernization to counter China in the Indian Ocean.

4.2 Securing Ecological and Riparian Rights

Tibetan self-governance is the only viable long-term guarantee for water security in South Asia. A Tibetan administration, culturally imbued with a reverence for nature,

would be far less likely to pursue the aggressive, mega-dam engineering projects currently championed by Beijing. Genuine autonomy would allow Tibet to manage its own resources, ensuring that transboundary river flows are governed by ecological sustenance rather than geopolitical leverage[6].

4.3 Dismantling the Nexus’s Legitimacy

China’s insecurity regarding Tibet is a major driver of its aggressive posture towards India. By actively supporting the Tibetan call for genuine autonomy on the global stage, India shifts the diplomatic pressure onto Beijing. It challenges the legitimacy of China’s presence on India’s borders. Furthermore, if the “Tibet card” is played effectively, China would be forced to redirect significant internal security resources to stabilize the plateau, reducing its capacity for external adventurism in collusion with Pakistan.

5. Policy Recommendations

To counter the China-Pakistan nexus effectively, India must adopt a proactive, multi- pronged strategy that centers on Tibet:

- RevitalizetheTibetPolicy:IndiamustmovebeyondtreatingTibetasamere “card” to be played occasionally. New Delhi should more overtly support the Central Tibetan Administration’s “Middle Way Approach” for genuine autonomy. This involves facilitating greater diplomatic access for Tibetan leadership globally and highlighting the ecological devastation of the Tibetan plateau under Chinese rule in international climate forums.

- StrengthenNortheastResilience:Accelerateinfrastructuredevelopmentinthe NER, particularly border connectivity and digital infrastructure, to reduce the sense of alienation among border populations that adversaries exploit.

- EnhanceCounter-NexusIntelligence:Deepenintelligencecooperationwith friendly nations (like the US, Japan, and Australia) specifically tracking ISI-MSS collaboration and arms trafficking routes into Myanmar and the NER.

- BuildLowerRiparianCoalitions:Indiamusttaketheleadinformingacoalition of lower riparian states (including Bangladesh and Southeast Asian nations affected by the Mekong dams) to present a united diplomatic front against China’s weaponization of transboundary rivers originating in Tibet.

6. Conclusion

The China-Pakistan nexus is a formidable challenge threatening the stability of Northeast India. However, the nexus thrives on the geopolitical anomaly of a militarize

Chinese presence on the Himalayas. The current status quo in Tibet is the root cause of India’s northern vulnerability.

Therefore, the quest for Tibet’s self-determination or genuine autonomy is inextricably linked to India’s national security. A stable, autonomous Tibet is the best bet against the pincer movement of the China-Pakistan axis. By shifting its strategic focus from merely managing the border to addressing the core issue of Tibet’s political status, India can transform the Himalayan geopolitics from a theater of perpetual threat to a zone of stability.

Bibliography & Sources

[1] Chellaney, Brahma. “China’s Salami-Slice Strategy.” Project Syndicate, 25 July 2013. (Discusses China’s incremental territorial claims, including Arunachal Pradesh). [2] Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. “Official Spokesperson’s response to media queries regarding denial of visas to Indian athletes from Arunachal Pradesh.” September 22, 2023. (Documents the ongoing diplomatic friction regarding China’s denial of Indian sovereignty over Arunachal residents). [3] Raman, B. “The Kaoboys of R&AW: Down Memory Lane.” Lancer Publishers, 2007. (Provides historical context on ISI’s attempts to foment trouble in India’s peripheral regions). [4] Small, Andrew. The China-Pakistan Axis: Asia’s New Geopolitics. Oxford University Press, 2015. (An in- depth analysis of the strategic cooperation between Beijing and Islamabad, including intelligence sharing). [5] “China’s Infrastructure Build-up in Tibet and its Implications for India.” Vivekananda International Foundation (VIF) Task Force Report, 2021. (Details the dual-use infrastructure development on the plateau). [6] Chellaney, Brahma. Water: Asia’s New Battleground. Georgetown University Press, 2011. (A seminal work on hydro- politics in Asia, focusing on China’s upstream control of the Brahmaputra). [7] Central Tibetan Administration. “The Middle-Way Policy.” (Official documents detailing the proposal for genuine autonomy within the framework of the PRC, emphasizing environmental stewardship).

(Views expressed are his own)

The author is the Director of the Tibet Museum under the Central Tibetan Administration.