BY MIKE STROBEL

His eyes are black as night. They have seen much.

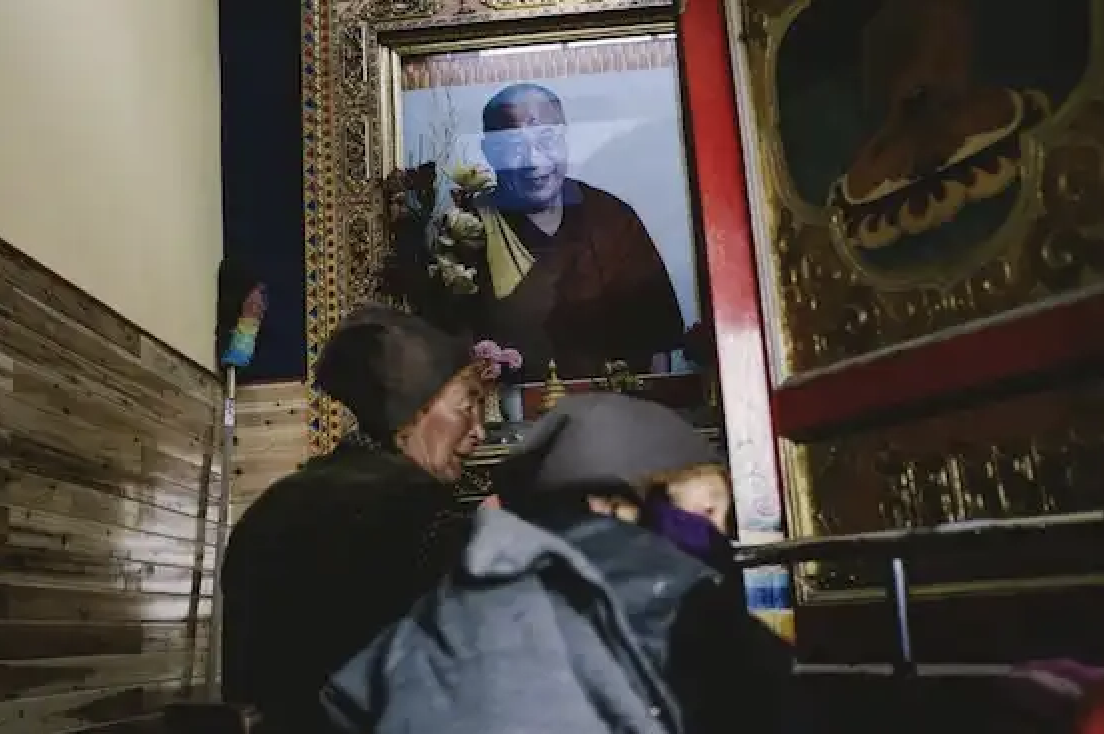

Stare into them. Drift back, to the Land of Snows.

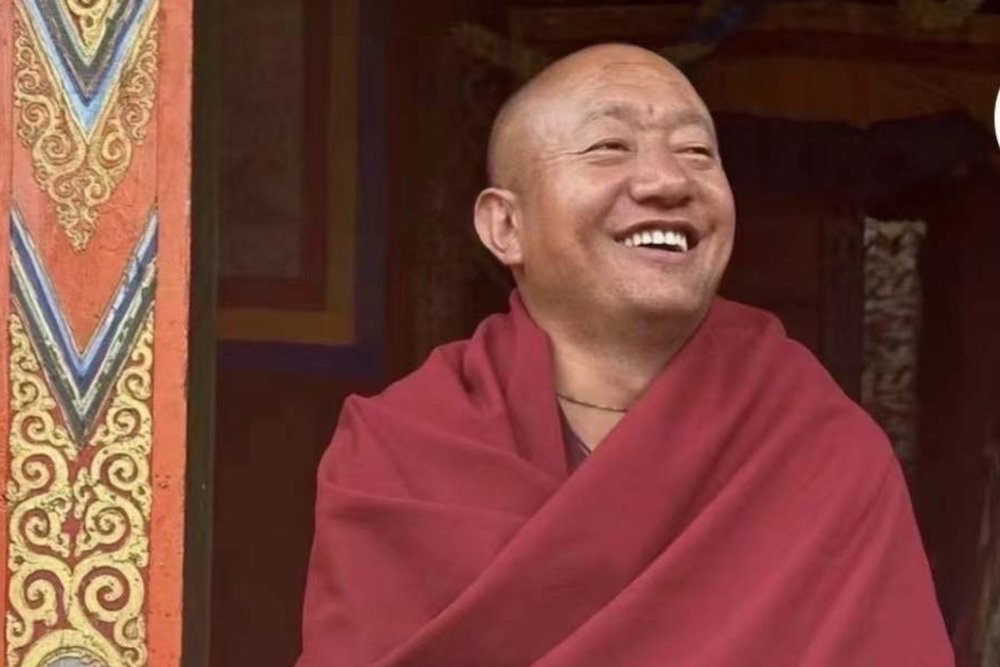

Pencho Rabgey is seven. He is a Tibetan monk.

“It was not for religion at first,” he tells me. “A monk’s life looked good. Everyone respected him. I bugged my father to let me go.”

So he grows up in the tiny monastery at Chungpa, his village in a Shangri-La valley in east Tibet.

He studies dawn ’til dusk and eventually takes the 253 vows of a full monk.”Thou shalt not kill” to “thou shalt not talk with your mouth full.”

He is 24, in 1959. For four years, he has been at the famous Sera Monastery in Lhasa, the ancient capital. China’s claws tighten on the mountain nation it claims as its own. Food is scarce. Fear is plentiful.

Pencho is “just a regular, simple monk.” But he is strong and he is picked to help spirit the Dalai Lama to safety.

They bring him guns. “But I cannot, I am a monk,” he says.

They suspend his vows. Same for 31 other monk-bodyguards. Before he knows it, he is draped in a shotgun, a British carbine and a machinegun.

Even the Dalai Lama slings a rifle. The cook has a bazooka.

They flee in the night, by foot and by pony.

The country crawls with China’s People’s Liberation Army.

It is the first time Pencho has had a good look at the Dalai Lama. Before, everyone had to avert their eyes.

Now, he is ordered to act naturally, not to draw attention to the man he guards.

He has discarded the maroon robes of a monk for the plain chuba of a civilian.

“Sometimes Dalai Lama said it was a hard time and asked if we were okay, if we were tired,” Pencho says.

From Che-La, the Sandy Pass, they take one last look at Lhasa below, too far for them to hear the rattle of Chinese guns, or the shelling of the Norbulingka summer palace.

Then they turn toward India. An early-spring sandstorm cloaks their escape.

For two weeks, the ragged band, growing as freedom fighters trickle from the hills, struggles in blizzards over the great peaks of the Land of Snows.

Through the clouds, they see the lights of Chinese sentries.

When the blizzards clear, snow glare blinds. Dysentery wracks them, including the Dalai Lama.

On March 31, they cross the border. India has built a bamboo welcome gate. Six Gurkhas stand at attention. One offers a scarf in greeting.

The Dalai Lama and Pencho Rabgey are free.

He is 36. No longer a monk. “If you cannot keep your vows, you had better give them up.” He met a girl. He and the beautiful Tsering have two kids, another on the way. They want a new life.

They ride the first Tibetan wave to Canada. It is a small wave. Only a few hundred settle here. Ten families, including the Rabgeys are in Lindsay.

It is hard to imagine Lindsay as a Little Lhasa, but immigration works in mysterious ways.

Pencho, a hard-trained monk, works 18 years in a casket factory. One of his kids is a Rhodes Scholar, another is a doctor.

“Everyone has helped us,” he tells me. “We are so happy to be free, to do what we want, say what we want.”

He is 69.

There are now 2,500 Tibetans around Toronto. A new wave began six years ago. They still don’t have a community hall, so they cram into the Ukrainian Cultural Centre at Bloor and Christie to celebrate the new Year of the Wood Monkey.

Here, in the coppery robes of a layman, former monk Pencho Rabgey tells me his story.

He avoids politics. He has built a boarding school in his home village and is still raising funds.

Tibet’s economy is better, but China’s grip remains strong.

Rigzin Dolkar tells me: “If you do nothing political, say nothing about the Dalai Lama, if you lead a very careful life, you will be okay.

“But that’s not enough, you know.”

She is helping organize the Dalai Lama’s trip to Toronto (www.kalachakra2004.com). It includes a SkyDome date April 25.

“We are essentially a people in exile.

“So to have our leader visit is very emotional.”

You do not have to be Tibetan. Or Buddhist. Or a monk, for that matter.

“The important thing,” Pencho says, “is a good heart.”

Hey, we could all do with a little of that.